If Cleopatra had a face that could launch a thousand ships, then Sócrates had a right foot that could sink a thousand.

A deep thinker, a heavier drinker and an unapologetic smoker, there will never be another footballer like him.

A Cultured Upbringing in a Military Regime

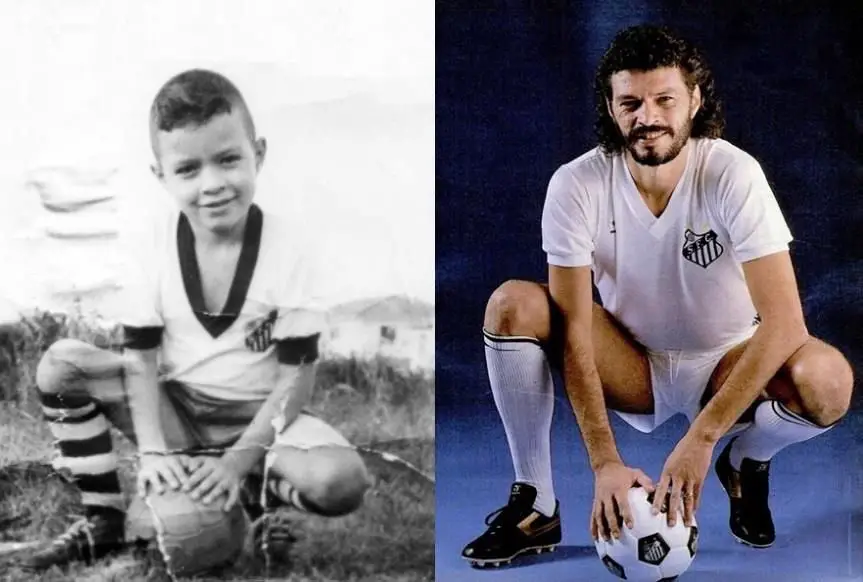

Sócrates Brasileiro Sampaio de Souza Vieira de Oliveira was born on February 19, 1954, in Belém, Brazil. Raised in a family of intellectual athletes, Sócrates always seemed destined for great things.

The name ‘Sócrates’ itself was a testament to his family’s appreciation for intellectual pursuits, inspired by the Greek Philosopher of the same name. Sócrates would grow up to live up to his namesake, an intellectual always striving to better himself.

I’d say he’d even have the original beat. As influential as the Greek philosopher was, the Brazilian Sócrates had a wand of a right foot. The Greek never scored 36 goals in a season from midfield.

Sócrates’ parents valued education and encouraged their children to excel both on the field and in the classroom. This upbringing fostered Sócrates’ passion for learning, a trait that would distinguish him from his contemporaries throughout his life.

Sócrates questioned the status quo from a young age:

“In 1964, I saw my father tear many books, because of the coup d’état. I thought that was absurd because the library was the thing he liked best. That was when I felt that something was not right. But I only understood much later, in college.”

The Brazilian Military coup d’etat of 1964, had taken away many of the rights of civilians and would leave a profound impact on Sócrates’ journey.

Football was a relaxing escape, but there was one problem with his laissez-faire attitude to the game. He was really good. It was easy for him. He didn’t look like a footballer, his gangly limbs giving a clumsy impression.

He had the look of someone that couldn’t trap a ball to save his life. Easily having grown beyond 6 feet by his early teens. But, contrary to appearance, he was frighteningly talented despite showing little care for training.

A combination of natural ability and intelligence, let him learn at a pace far beyond his footballing peers, which allowed Sócrates to spend the time he would be training studying.

The second he turned 18 he had a contract on the table. Botafogo were desperate to have him in the first team.

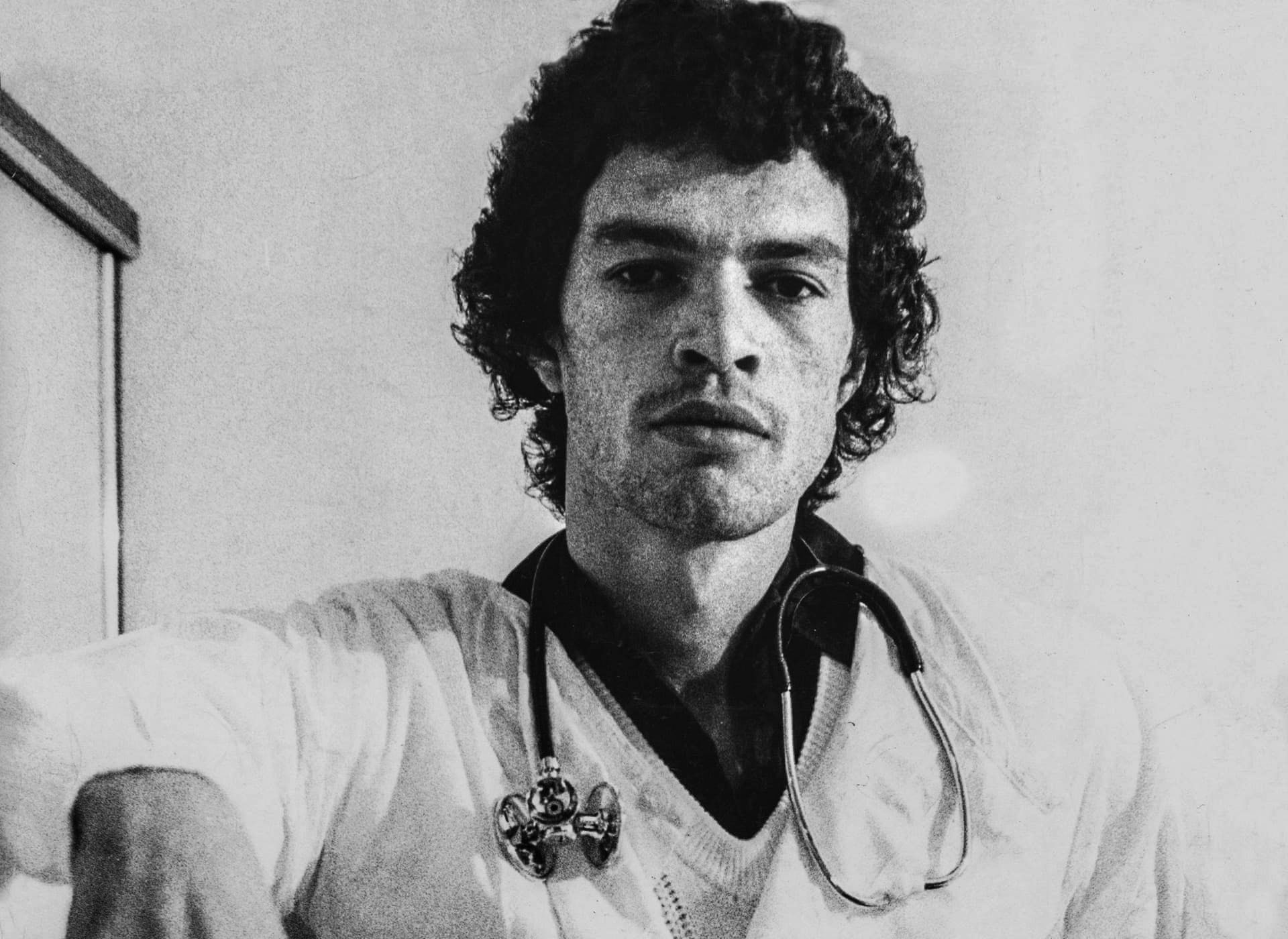

Medicine, Activism, Football – In That Order

Sócrates was nonplussed. Football was still just a pastime to him, despite his ability.

Botafogo were so convinced this boy was destined for greatness, they made an agreement specifying that Sócrates didn’t have to train, as long as he turned up to play on match days.

This allowed him to remain a university student.

The step up to playing in the Brazilian first division hardly phased him. After all, this was simple stuff compared to an appendectomy.

By 1976, he’d established himself as a key player for Botafogo, scoring 11 in 42 games in his early breakthrough seasons (though he was best known for his assists).

Sócrates, now 3 years into his degree, and professional football career would find himself prone to vices both footballers and intellectuals alike regularly succumb to. Drinking, smoking and partying began to fill his days and nights when he wasn’t studying.

Botafogo would try to exert power over him but found it easily rebuffed. Sócrates was not one to bow to pressure from those in charge.

He held a unique leverage over his employers thanks to his insistence that this football gig was only temporary. He was just playing until he finished his medical degree. Sure enough, a year later, he earned his Bachelor’s degree and prepared to make arrangements to leave the club and find a job as a Doctor.

Sócrates was a man of principle, empathy and unwavering in committing to his beliefs. But as the old saying goes: ‘Every man has his price”.

Botafogo, convinced of his talent, offered him a mammoth contract, eclipsing anything he could hope to earn in the medical field.

Recognising he’d be a fool to turn down such an offer, he signed the contract. His medical career would have to wait.

This wouldn’t stop his love affair with booze and cigs however, nothing could make him give them up.

His next season was his best yet, scoring 10 in 22 earning him a move to the Corinthians.

A Cult of Personality

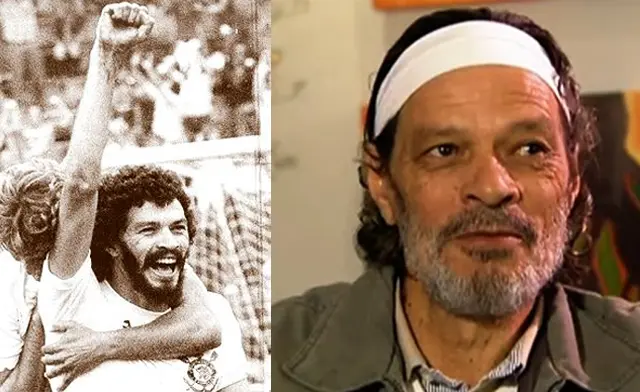

Sócrates’ time at Corinthians proved fruitful for his ambitions in more ways than one. He’d win a state championship and earn his first call-up for the national side. Up till now, the national side had been hesitant to play him due to his hedonistic lifestyle and scraggly appearance.

But the achievement Sócrates would no doubt be most proud of, was inspiring the “Democracia Corinthiana” movement. Alongside his teammates, he advocated for players’ rights and the democratisation of the club, allowing players to participate in decision-making processes.

Everyone at the club, from the president down to the cleaners and the kit man, had an equal vote. Players all received the same win bonus, and the staff would then receive a percentage to be shared amongst them.

The movement soon transcended football. With the side flushed with tens of millions of fans, the general public were becoming more aware of institutionalised corruption that was rife within football and the government. Hi

But, before things progressed off the pitch, Sócrates would deliver one of his greatest ever on-the-pitch moments. It was the 1982 Spanish World Cup, and Brazil faced the USSR, Sócrates very much the political antithesis of Brezhnev’s Soviet Union.

With 75 minutes gone, Sócrates picked the ball up halfway inside the Soviet half. Striding forward, he hurdles one challenge, before dropping a shoulder to beat a second. With the goal in his sights, he unleashed an almighty shot that rifled into the top corner.

It was a goal that Sócrates would later describe as “an endless orgasm.”

Brazil would go on to lose to Italy in the second group stage.

But, Sócrates wouldn’t have long to dwell on the national side’s failures. His activism soon set the stage for a battle of ideologies.

A Politically Charged Rivalry

Back to club football, the whole of Brazil’s attention turned to the state championships. Corinthians were poised to face São Paulo, in a battle that was symbolic of political tensions at the time.

The democratic movement at Corinthians had now fully captured the hearts of fans, the people no longer believed the government’s lies of life being as “good as it could get”.

The match between the two sides was shrouded in political symbolism. São Paulo, traditionally a team supported by wealthy conservatives, and Corinthians, the working-class majority.

The atmosphere was hate-filled. Corinthians won 4-1 on aggregate, but the most memorable moment of the match came not from a goal, a pass or a referring decision, but from a celebration.

After scoring, Sócrates turned to face the crowd and stood still, raising his arm to the sky with a closed fist, imitating the rebel salute. The movement was real.

The next year, it happened again. The same competition, the same two teams, the same final. Sócrates scored again, and just like before, he raised a clenched fist to the sky in protest of the Brazilian regime.

The movement had now spread far beyond just Corinthians fans.

For too long the rich had been getting richer, and with Brazil suffering from record inflation, any change in austerity seemed tragically unlikely with the current regime in place.

European sides came knocking for the revolutionary, but Sócrates felt he had a job to do in Brazil. He owed it to the people to stay and be a symbol for change.

Sócrates was more than just a Corinthians player, he was a sanctified leader, a cult of personality aiming to strong-arm the government into change by capturing the hearts of the masses.

Rallies, protests, strikes and marches began to take place in a push for democracy, with millions turning out for the cause. The people wanted democratic process. The people wanted a vote.

Sócrates and his Corinthians wore yellow accessories in games in solidarity with the movement.

An Ultimatum

In April of 1984, a Congressman brought forward a bill that would grant the people a vote in the upcoming election. Soon, Sócrates was centre stage at rallies, speaking to the masses and being cheered like political revolutionaries before him. He had used football to mount a serious uprising.

But, revolutions rarely achieve their goals in a matter of a few years, and for Sócrates’ trotsky-esc revolution, pressure from the military government would prove too strong.

Sócrates had received a contract offer from Fiorentina in 1984 and announced at a rally in front of millions of supporters that he would stay at Corinthians if Congress approved the Constitutional Amendment, a bill which would restore direct elections to decide the President of Brazil.

If the bill passed, Sócrates would see this as a sign of the country’s progression, and stay in Brazil to continue his activism. But if it failed to pass, he’d move to Italy in protest.

Sadly for the revolution, it didn’t pass, and Sócrates was bound for Italy.

The military regime had pressured politicians into abstaining from the vote, as the bill fell short by 22 votes, thanks to 113 ballots not being cast.

Sócrates left in an act of rebellion, but quickly struggled in Italy. Playing in a wealthier right-leaning country, struggling with injury and continuing to smoke, drink and party, the Italians quickly grew to dislike the Brazilian. Just a year later he returned to Brazil.

The Brazil he returned to, however, was a very different political landscape.

Emptiness in Fulfilment?

As much as his powerplay had failed to push the direct election bill through Congress, he’d stirred up plenty of support for the cause. By his return in 1986, Brazil’s transition from a military government was already underway.

The constitution was amended as elections for a National Constituent Assembly were called, with the aim of drafting and enacting a new democratic constitution.

Come 1988, this assembly had adjourned, restoring civil and public rights such as freedom of speech, independent public prosecutors (Ministério Público), economic freedom, direct and free elections and universal healthcare. It also de-centralized government, empowering local and state governments.

Sócrates had done it. What had started as a movement to treat contracted players and staff at Corinthians fairly, had snowballed into a full-blown rebellion that had come out victorious in the fight against a dictatorship.

He’d done what so many revolutionaries before him had failed to do. He’d beaten oppression with idealism.

Sócrates will forever have a place on the football pitch as one of Brazil’s greatest players. But he is the only footballer to profoundly change hundreds of millions of lives for the better.

By 1989 he was back at Botafogo, now in the Serie B. Following a season of cameos for his childhood club, he retired to fulfil his dream of practising medicine, but promptly grew bored.

He would spend the rest of his life flitting from venture to venture. Political projects, stints as a surgeon, TV and Writing took his fancy and even coaching semi-professional football.

Like all geniuses, he grew bored very easily.

Sócrates was the catalyst, the beacon of hope the people needed to incite change. He will always be football’s greatest revolutionary.