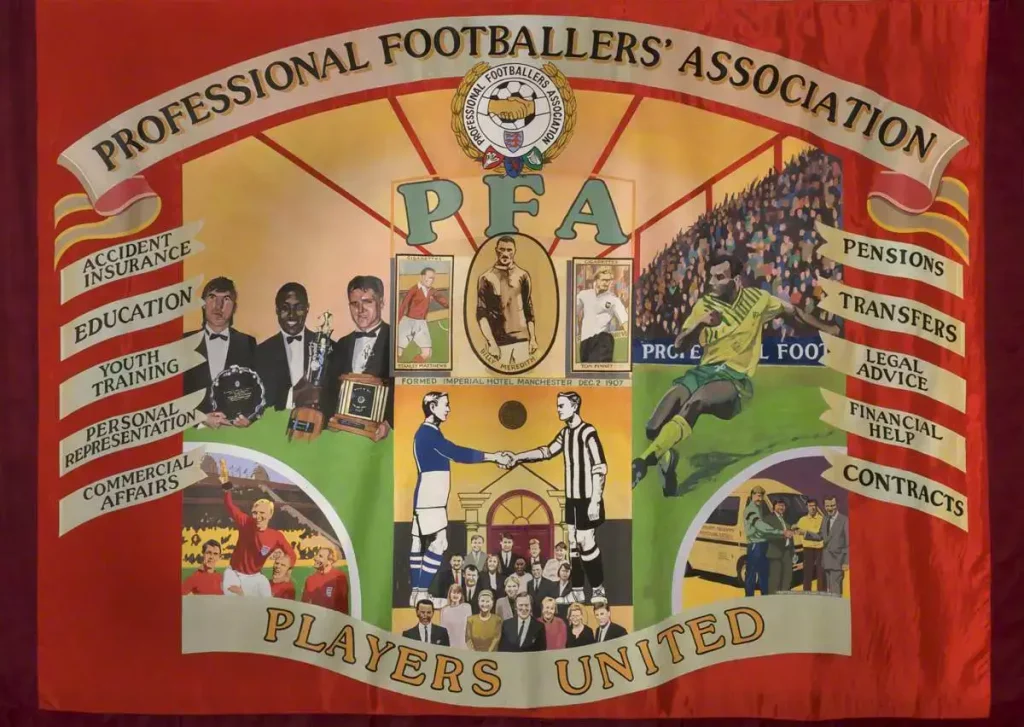

Football players in England and Wales are represented by a trade union known as the PFA (Professional Footballers Association). There are over 5,000 members of this professional sports trade union, which was founded in 1907.

Current and former footballers, scholars, and coaches in the Premier League, the FA Women’s Super League, and the English Football League are all members of the Professional Footballers Association (PFA).

Their mission is to empower footballers to realize their value as people, not just players, and believe in the unifying power of football in society. Their services include educational, financial, and well-being support and protection of players’ rights. Let’s review the formation of the PFA after initial attempts in 1898 failed.

The Birth of the PFA Union

Facing up to the powers that were, they risked total banishment from the game: this is the story of the players who fought for financial and contractual justice for all.

The £4 a week maximum wage, set in 1900, meant that no player, regardless of talent or experience, was free to negotiate higher earnings with his club, whether by bonuses or signing-on fees.

Although the new ceiling was aimed mainly at the best-paid players, there was only token adherence to the new rule by the richer clubs. Some could afford ‘better terms’ and were determined to pay them in order to establish themselves in the top echelon.

Between 1901 and 1911, at least seven clubs were investigated and punished for financial irregularities, such as paying players’ under-the-counter’ wages.

Many other clubs were considered guilty but escaped punishment, having successfully disguised the money as ‘presents’ or payment for extra duties. Some clubs were less fortunate.

Middlesbrough, for instance, had been elected to the football league in 1899 and reached Division One in 1902. One year later, at the cost of £10,000, they opened one of the finest grounds in the country, Ayresome Park.

However, the expenditure stretched the club so much that a few years later, it struggled with falling attendances, heavy financial losses, and poor on-field performances. In two years, they failed to register a single away win.

In February 1905, in an attempt to improve their situation, the club startled the football world by paying a record £1,000 to Sunderland for their ace striker Alf Common.

The average transfer fee was about £300 to £500. The furore led to an investigation of the account books by the club’s shareholders, who alerted the FA.

On November 17th, 1905, Middlesbrough’s directors admitted to making illegal payments to players worth £400 over the previous two seasons and creating fictitious accounts to conceal their actions.

The FA fined them £250, and 11 of the 12 directors were suspended until January 1st, 1908. In addition, one of the players, Teddy Gittens, was fined £10 for making false statements. More significantly, the nascent Players Union would be the case of Manchester City.

City won the FA Cup for the first time in 1903. Still, the following season, after anonymous accusations of attempted bribery against their captain and star player, Billy Meredith, the complete cup-winning side was suspended and banned by the FA from ever playing for City again.

Club directors (including Joshua Parlby, one of the original Football League founding members) were banned for life, and the club was fined to within an inch of survival.

Meredith served an 18-month suspension and was eventually transferred to Manchester United, but he was now determined that players should get organized to fight their case for contractual and financial freedom.

Within a few months of returning from suspension, on December 2nd, 1908, he convened the first meeting of a new Association Football Players’ Union at the Imperial Hotel, Manchester.

Among those present were seven Manchester United players, two Manchester City players, plus representatives from Newcastle United, Bradford City, West Bromwich Albion, Notts County, Sheffield United, and Tottenham Hotspur.

Soon after, Manchester United goalkeeper Herbert Broomfield was offered the first full-time union secretary job with a salary of £150 per annum for three years.

The new union saw its aim as not just financial and contractual freedom but also the creation of a body that would help all professional footballers, no matter their station, to obtain justice in disputes with their clubs and restitution in the case of injury and punishment.

The case of George Parsonage, a Fulham player suspended from football for life in 1909 for daring to ask for more than the regulatory £10 signing-on fee, was one particularly high-profile case that galvanized his fellow professionals to join.

The union started a petition on his behalf that drew some 1,322 signatures. In the same year, following the advent of the Liberal Government’s Workmen’s Compensation Act and the subsequent establishment by the Football League of the Football Mutual Insurance Federation, the legal casework of the union would increase dramatically.

But the union decided to affiliate with the National Federation of Trade Unions, that brought it into direct conflict with its parent body, the FA.

Fearing members would one day resort to strike action, the FA withdrew its support from the union and demanded that every player resign from it or else be banished from the game. Manchester United’s players, led by captain Charlie Roberts, refused and were promptly suspended by the club.

They became the focal point for a summer-long battle of wills, culminating in a stand-off at the beginning of the 1909/1910 season. With the League clubs facing the prospect of no games, the FA backed down, and the Manchester ‘Outcasts,’ as they had been dubbed, won a famous victory.

The union survived – but only just and at the expense of its wider Trades Union links. Between 1908 and 1914, the numbers of men and women assisted by the union would run into hundreds, and the amount of money disbursed into thousands. Still, because it could wield no industrial muscle, its impact on wages and contracts remained minimal.

This was made evident in 1912 when it backed Herbert Kingaby, an ex-Aston Villa player, in his attempt to have the standard contract declared a restraint of trade.

The High Court case was lost, and the union was almost bankrupt. Subsequently, the conditions under which professional players labored would continue to be a source of bitter contention.

The 1920s – Pulling the Crowds

As players made their way from the battlefields back to the playing fields, the end of the Great War saw an age of enormous growth for the game – and players’ rights.

The First World War saw the Players Union close down as professional football ceased, and hundreds of players joined the armed forces. Football continued, but only on a part-time basis. When the war ended in 1918, most pre-war union officials were still in uniform and abroad. The union would be revived in a strange way.

In 1919 a group of London-based professional players, angry at the lack of concern shown towards professional footballers as they returned from the war, put forward a more militant union proposition, with traditional industrial unions becoming involved.

A meeting was convened at the Memorial Hall, Farringdon Street, with HWT Hardinge, the Arsenal and England international, presiding. As a result, approximately 60, mainly southern, pro players formed the Professional Football Players’ and Trainers’ Union.

Having arrived late from Manchester for the meeting, Charlie Roberts took action after he heard that the FA would move against the new organization because it was perceived as militancy. Assuring the FA that the old union could continue on prewar terms, he re-established the Players Union in Manchester with the London men’s agreement.

At the ninth AGM, in August 1919, the membership fee was raised to 1s, and the secretary, Harry Newbould, was awarded a £7 weekly wage. Where the football industry was concerned, the gloom and depression of the war years were shaken off with almost indecent haste.

Its appeal to working men and women would be symbolized by the building of the new Wembley Stadium. It was designed to hold 100,000, but the first cup final attracted a crowd of over 200,000, with chaotic consequences!

Within two years of the Armistice, the Football League had expanded to four divisions, and by 1923, the pre-war complement of 40 teams had risen to 88.

The bulk of the Southern League had been absorbed to form the Third Division South; thus, the Football League reigned supreme in England and Wales and, for a year or so, made considerably more money than ever before.

In February 1920, the third round of the FA Cup drew more than half a million spectators, paying over £33,000 in gross receipts. Grounds were collapsing under the weight of spectators.

There were scores of injuries at Chelsea when a roof upon which people were standing collapsed onto spectators below. Even middle-ranking teams were reporting record takings.

For instance, Bradford City finished the season in mid-table that year and was knocked out of the cup in the second round, yet they registered gross takings of more than £35,000 and profits after all expenses and taxes had been deducted of £22,000.

Burnley was another small club reaping a financial harvest, though in their case, it was due to success on the field. The Clarets were League runners-up in 1920, champions in 1921, and third in 1922.

During their championship season, they made a clear profit of £13,000! Of course, inflation played its part. Admission fees went up from 6d to 1/- but attendances were now massive, as men flocked back from the forces into civvy street, repossessing the factories and the towns they had temporarily handed over to their womenfolk.

Football was the obvious beneficiary of this return to normal, although, within a year or so, other entertainments would begin to compete with a vengeance.

For professional footballers, the boom receipts took some time to filter into their wage packets, but when they did, it must have seemed like the dawn of a new age.

In 1920 the maximum wage stood at £4.50 a week. For the 1920–21 season, it doubled to £9 a week, reflecting how much money clubs were making in the post-war boom.

Alas, the dawn was a false one. With economic recession looming, many clubs had overreached themselves with expensive ground extensions – not to mention ever-rising transfer fees within a year or two.

In 1922, with the Football League’s connivance, they decided to cut wages unilaterally. Players’ contracts were torn up. Faced with its first big challenge, the union acted decisively.

It mounted a test case in law to question the legality of the League’s wage-cutting decision. The case chosen was that of Henry Leddy, a Dubliner, center-half, and captain of Chesterfield.

Leddy had signed his contract in March 1922, guaranteeing him £9 a week all year round until May 1923. However, the League’s resolution to cut wages came a month later.

Thus Leddy had refused to sign a new contract and had, it was announced, “brought his action to contest the right of the club or the Football League to break his contract under the common law of the land.”

The case was eventually won. The players had now established the sanctity of their contracts, although their general position where pay was concerned had hardly improved.

In the mid-1920s, a sliding pay scale was introduced by many clubs. New players might start on £5 a week and earn annual rises of £1 a week over four years. Thus, a new maximum wage of £468 a year was created.

But the sliding scale gave club management flexibility in dealing with players, and many clubs used it as a device to intensify competition between men in the same club and depress wages.

It was a decade that also saw the gradual grinding down in many other ways of the professional player. The union, however, was slowly beginning to establish itself.

In November 1929, on the 21st anniversary of its reformation, it was financially sound, situated in new offices at 133 Corn Exchange Buildings, Hanging Ditch, Manchester, and even had a female personal assistant appointed to the union secretary. The fight-back could now begin.

The 1930s – A World in Motion

The game went global with the launch of the World Cup, but British football remained in a league of its own as players fought for better contracts and war loomed again.

As professional football expanded worldwide, the British game, because of its massive popularity at home, refused to get too closely involved, deeming the standard of play abroad as too poor. Perhaps they had a point.

In 1933 and 1938, lowly amateurs Moor Green from Solihull won the Verviers Trophy, in which European professional sides faced amateur teams from England.

In 1933 they beat the mighty Dutch side Eindhoven, and in 1938 they attracted their biggest-ever crowd when more than 15,000 watched them lose to Ajax in Amsterdam’s Olympic Stadium. Likewise, no British football association sent a team to FIFA’s new World Cup when it started in 1930.

The FA had joined FIFA, the international football organization, in 1906, but the relationship was fraught with disputes.

All four British football associations withdrew from FIFA in the 1920s, ostensibly because of an unwillingness to play against the countries they had been at war with and as a protest against ‘foreign’ influences on what was considered Britain’s game.

This meant that England did not enter the World Cup until the 1950s. At home, ‘international’ generally meant Home International; the competition regularly fought out between England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland, with the winner being declared the unofficial world champion!

However, playing for England earned those involved very little. For instance, Ernie Blenkinsop was a top English professional who signed for Sheffield Wednesday in January 1923.

During the next 11 years with Wednesday, he made more than 420 appearances and won two First Division championships. Then, in March 1934, Ernie moved to Liverpool for £6,000.

Throughout his career, he collected 26 full England caps. Indeed, he set a record for consecutive international appearances, playing in every England game from 1928 to November 1933, and he captained the national team on four occasions.

His wages were capped at the maximum salary payable to footballers (£8 per week during the season), and he received just £6 for each England appearance.

It’s been claimed that for a Wembley international in the early 1930s, the FA paid the band that provided the pre-match entertainment more than they paid the England team. The formation of new professional leagues in France and the USA in the 1920s and ’30s did offer a financial alternative.

While the headlines of the popular press blared out concerns about the “menace” to British football posed by these new leagues beyond its shores, the Players Union was arranging for its members to travel to France for trials on good financial terms, even though many of the men were still registered to play only in Britain.

Ironically, at about the same time, the union approached the Ministry of Labour to complain about ‘alien’ players coming to Britain and taking British players’ jobs!

However, the retain-and-transfer system meant that players needed permission to leave. If they broke their contracts, they faced permanent suspension on returning home, and few top players could risk that.

Worse was to come. As the inter-war years progressed, the downward pressure on players’ wages at home intensified. With each succeeding slump in general trade, there were calls from various clubs for a reduction in wages across the board.

Although no such reductions were ostensibly made, the license clubs had to squeeze down the wage bill was exercised with ever more ingenuity.

During the 1930s, Grimsby and Sheffield Wednesday pioneered an ‘incentive’ scheme in which the best players were guaranteed a weekly wage of £6 a week with £2 extra if they kept their first-team place.

Thus, you could only earn the maximum if you played in the first team. Being dropped into the reserves meant a significant loss of wages.

If you cannot secure a place even in the ‘stiffs’ (an unkind word for the reserves), your pay might drop to £4 a week. Once out of the first and second teams, the extra bonuses for wins and draws disappeared.

In an industry where one’s form and selection was often a matter of tactics, individual judgment, or perhaps of simple fate, such a system of ‘performance–related pay’ engendered insecurity, anxiety, and often deep discontent among playing colleagues.

Indeed, suspicion, resentment, and a sense of injustice were the natural by-products of the system, a system that players had no say in formulating or applying.

By 1939, according to the PFA, fewer than 10 percent of players were in the ‘maximum’ earning bracket, a figure not dissimilar to that achieved in 1910. However, the actual number may have been higher, as more men received it than were guaranteed it by contract.

Second and Third Division players never earned the maximum wage, and there were many examples of even the best men making no more than £7 in season and £4 in summer.

By 1932, the number of players being forced to seek unemployment benefits had dramatically increased, not because there were fewer positions for them at clubs, but because clubs were holding more and more men on their retain-and-transfer lists while paying them nothing at all, determined to make something from their departure they thus had a pool of free labor at their disposal.

With most clubs unable to afford fees, no matter how small, these men stayed out of work and thus had to claim the dole.

Nevertheless, the union gradually rebuilt its membership. It expanded the help it gave to players in need while trying in vain to establish proper football insurance for players and even a pension on retirement.

In 1937, with membership approaching 2,000, the union pushed for an increase in the retaining fee (an unofficial minimum wage) from £208 to £260. The League rejected this, along with a request for a £1 increase in the maximum salary.

Finally, in 1939, the union drew up a long list of demands, including contract and wage reforms – but, fortunately for the League, war intervened just as the membership’s militancy reached a climax.

The 1940s – The War Effort

Football is forced to take a back seat as war rages at a substantial financial and professional cost to many players. But the fight for pay and conditions gets a boost when peace returns.

Unlike in 1914, when so much criticism had been heaped upon players and clubs for continuing to play once the First World War hostilities had commenced, the beginning of the Second World War saw swift, decisive action taken that left no one in any doubt as to what the priorities were.

The league program was immediately halted, and when football recommenced in the form of a reorganized competition in late 1939, it was clear that what was being provided was’ essential entertainment.’

The men at the very top of the profession were now seen as entertainers in their own right, and their privileges — the freedom to leave their army units to play in international and representative matches — appear not to have been resented.

Morale was considered to be as important as weapons. What’s more, many former professionals were given particular tasks related to fitness training within the armed forces, and their contribution was immense.

Like the First World War, however, professional footballers ceased to exist as legal entities: their contracts were canceled, and they were no longer covered for injury under the Workman’s Compensation Act.

However, the football clubs themselves continued to operate, and, as in the 1914–18 war, they retained their hold on players whose contracts they were no longer obliged to honor.

However, league rules regarding soccer player registration were relaxed. As a result, players were permitted to play for different teams, sometimes even within the same competition.

Disruption was so significant that some clubs could not always count on having 11 men available on match day, and many a supporter found his dreams coming true as he stepped from the terrace onto the pitch to play alongside his heroes.

Nevertheless, many footballers were now seeing the best years of their playing lives gradually eroded. Six years is a significant slice to take from anyone’s career. Still, considering that a professional footballer’s ‘life’ generally lasts no more than ten years, the Second World War ruined the hopes and dreams of hundreds of professionals.

Those not in the forces, working in factories, munitions, or reserved occupations, continued to turn out each weekend.

Still, it was twilight, a part-time career and, as a letter to union secretary Jimmy Fay from Jimmy Guthrie, Portsmouth captain and future chairman of the union, written in early 1943, demonstrates, there was a certain amount of resentment building up: “The football player has been hard hit and I am sure no one will deny that 30/- is a very meagre sum.

Many players are having a tough time making ends meet. All we ask for is a square deal. Unfortunately, I don’t think we are getting one.”

The most significant difference between the two wars would be the fate of the union. Unlike in 1914, when it had more or less ceased to exist, in 1939, chairman Jimmy Fay ensured that the PFA remained intact.

He closed the Manchester office and took everything back to a small room above his sports shop in Southport, where he continued to work unpaid.

As a goodwill gesture, he let players claim back a portion of their subscriptions from the union to tide them over, as football had become regionalized and full-time pay ceased.

Fay worked extremely hard and was determined to hit the ground running when the game restarted, and nothing less than wholesale reform of players’ conditions was his goal.

He traveled the length and breadth of the country, keeping in touch with members and helping out where he could. Almost as soon as the war ended in 1945, with the resumption of a full league programme imminent, the union put in a demand to the Football League for an £8 match fee minimum.

When this was rejected, it drew up a further plan. A £12 a week maximum and £5 minimum weekly wage were demanded, along with amendments relating to existing contracts and accident insurance.

The Football League rejected this and offered only pre-war wages, effectively reneging on earlier promises. The union consulted its members, and on November 5th, the result of a strike ballot was announced: 62 clubs voted for strike action, and two were against it.

The stoppage was set for November 19th, 1945, but at the last moment, the union-management committee accepted a £1 increase on 1939 pay levels. For the first time, however, bonuses of £2 for a win and £1 for a draw were introduced.

Although this was disappointing, something significant had happened, indicating that the times were changing radically. Angered by the latest climbdown, union delegates pressed for firm action the following season.

In 1946, after further unsatisfactory negotiations, the union declared a strike – only to find that recent legislation prevented it. The Industrial Relations Office of the Ministry of Labour had read about the proposed action in the newspapers and alerted both sides to the War Emergency Act.

The new Labour Government, desperate to keep production up at a critical period of reconstruction, was doing all it could, with TUC cooperation, to prevent industrial stoppages.

Thus, strikes were illegal and compulsory arbitration with government involvement was now the only option. For the union, it turned out to be a godsend.

In March, the Ministry of Labour referred the whole dispute to the National Arbitration Tribunal, and two weeks later, the PFA was granted most of what it wanted: a £12 maximum during the playing season (£10 in summer); a minimum wage of £7 during the playing season and £5 during the summer for all full-time players over the age of 20.

It was the beginning of a new age for the union, as it was now involved in face-to-face negotiations with the league concerning everything from pay to pensions – and this time, the employers could not just walk away!

The 1950s – Smile You Are On TV

As football was regularly brought into the nation’s living rooms, the union faced upheaval and overhaul and took its first steps into the wider union movement.

Football on TV had a long gestation period. On April 9th, 1938, two years after regular television broadcasts were first launched by the BBC, the world’s first live television pictures of a soccer match were screened.

On February 8th, 1947, the BBC showed a fifth-round FA Cup match between Charlton Athletic and Blackburn Rovers.

Although the Football Association continued to allow international games to be shown on television, the Football League was generally reluctant to allow either highlights or live coverage of league matches, as it feared it would harm attendance.

The launch of BBC’s Sportsview in 1954, along with the arrival of floodlit football in England in the mid-1950s, increased the sport’s attractiveness to viewers. The widespread use of floodlights first involved the PFA, where the question of extra payments to players was concerned.

Chairman Jimmy Guthrie insisted that the players get extra payment for these night-time appearances and later brokered a deal that saw each man receive £2-3 per TV match.

This latter agreement would unwittingly lead to the union receiving a bonanza from TV rights some decades later. However, the 1950s would mainly be noted for Jimmy Guthrie’s attempt to restructure the union to transform it into a typical industrial trade union with a base in London and full-time staff.

In 1955, Guthrie succeeded in taking the PFA into the Trades Union Congress, the first time it had been a part of the broader union movement since 1909.

At that year’s TUC National Conference at Blackpool, he made a speech in which he described professional players as being “little better than slaves.” Though it was tremendous publicity for the union, it was resented by many within the organization, who felt it demeaned the profession.

Veteran secretary Jimmy Fay was generally opposed to Guthrie’s restructuring plans and resisted the latter’s plans to buy new offices in London.

With Fay’s retirement imminent and the need to find new premises for the union offices (the old one was still over Fay’s Southport shop, which he was selling), there was a tug-of-war between Guthrie and the rest of the committee as to where the new offices should be — Manchester or London?

Fay moved quickly in early 1953 to secure two rooms in the Corn Exchange Building, in Manchester’s Hanging Ditch (the same building in which the union had had offices before the First World War), describing them to the rest of the committee as perfect: “It would be impossible to find offices in London to compete with them.”

It marked the beginning of the end for Guthrie. He increasingly saw himself as something apart from the rest of the union committee.

He placed great store in knowing the ‘right’ people. With the Law Courts, Fleet Street, and Westminster just a taxi ride away from his small rented flat, he could spend his days and nights rubbing shoulders with men and women more to his liking.

He later commented, “Most of the action in those vital days was centered around London, where I was in constant contact with MPs, solicitors, barristers, and insurance brokers, while Jimmy Fay and his two girl typists looked after the day-to-day administration.

Most of their time was spent in receiving and acknowledging subscriptions because players had begun to contact me directly instead of going through other channels whenever they had a grievance to air…”

Jimmy Guthrie’s achievements during his years as paid chairman were many. He secured regular maximum wage increases, a provident fund, a players’ charter of rights, and a union magazine.

His objective was to create for pro footballers an all-embracing membership package including insurance, healthcare, legal advice, and pensions, as well as pressing for the union to have a say in the running of the professional game.

In many ways, he was perfect for the immediate postwar years, when the reforming Labour Government involved itself more directly in labor relations and thus gave smaller unions such as the PFA a helping hand.

But his methods were often slapdash, and his tendency to commit scarce union funds to schemes that sometimes flopped worried men like Fay and the equally careful Cliff Lloyd.

Following a disagreement over the Players’ Block Insurance Scheme, Guthrie was voted off the management committee, ostensibly because the union’s rules did not allow for a paid official other than the secretary. It was sudden and rather sad.

However, his successor, Jimmy Hill, was another man in a hurry, and within months, the PFA was pitched into some of the most controversial battles in its history.

First came the Sunderland Affair, in which several Sunderland players were suspended permanently from football after refusing to answer questions relating to ‘under-the-counter’ payments.

Hill and his committee challenged the FA, demanding a wide-ranging inquiry and starting a petition among players, calling on any who’d received illegal monies to sign it.

Eventually, the FA backed down, and the Sunderland men were fined and allowed to play again. However, the affair highlighted the extent to which the old maximum wage became an anachronism.

Clubs were straining to pay men wages more closely approximated their commercial worth. At the same time, the players were increasingly impatient with their lack of bargaining power under the old restraint-and-transfer system. Something had to give.

The 1960s – Ain’t No Stopping Us Now

While England’s players triumph on the pitch, their union scores historic victories that will change their plight beyond belief – but they nearly bring the game to a halt in the process.

The lifting of the maximum wage in 1961 is often seen as a pivotal moment in the history of professional football in this country and with good reason.

The campaign that preceded it caught people’s imagination in a way that no other such football battle had before or has since, with much of the attention centering on Jimmy Hill, the charismatic successor to Jimmy Guthrie as union chairman.

With his comparative youth and gift of the gab, not to mention that godsend to all football cartoonists, his long, piratically bearded chin, Hill instantly became the acceptable face of modern professional football.

By sharp contrast, the grumpy old men of the Football League, with their cigars, Homberg hats, and tendency to talk in riddles, seemed like throwbacks to the inter-war years.

The lifting of the maximum wage was one of a raft of demands put before the Football League by the newly dubbed Professional Footballers’ Association, calling primarily for the abolition, or at least radical reform, of the hated ‘retain and- transfer’ contract system.

The players desperately wanted the freedom to negotiate their contracts and the chance to walk away freely if no mutually acceptable terms could be agreed upon.

Backed by a 100 percent strike ballot result and knowing he had the media as well as the general public on his side, Hill threatened to bring the game to a complete halt for the first time in its history.

Resent the situation as it might, the Football League was seen as the villain, and to have simply walked away, as it had done so many times in the past, was now out of the question.

Nevertheless, it was facing a stark moment of truth – the abolition of the transfer system by which players could be bought and sold. Many clubs felt the system was their lifeline.

Smaller clubs feared they would be unable to continue in business without the chance to sell players. On the other hand, the larger clubs considered their stars as substantial investments, major assets on the balance sheet. So it was unthinkable that the system might end.

This fear of the unknown led the League to pull off a shamefully audacious coup.

Like the players’ representatives, the Football League management committee gave the impression that they were free to negotiate and any agreement between the two parties would be binding.

So when League president Joe Richards finally shook hands with Jimmy Hill in full view of the nation’s press as a last-minute ‘historic agreement’ was reached, Hill thought he was shaking hands on the deal there and then, which included radical changes to the contract system as well as the lifting of the ceiling on wages.

It was the latter item that hit the headlines the following day. Fulham chairman Tommy Trinder had claimed that he would pay his club captain Johnny Haynes £100 a week if the maximum were scrapped. The press chose to concentrate on this, while the rest of the deal seemed to have been forgotten.

Some months later, a full meeting of League clubs threw out the key aspects of the ‘agreement’ relating to contracts – in effect reneging on what Joe Richards had brokered – the publicity caravan had moved on.

The fans had their football back, the players had their ‘unlimited’ wages (although few would earn anything like Haynes), and any thought of mounting another strike campaign had to be shelved (particularly as participation by the top players was key to good publicity and by now they would have been risking considerably more in terms of wages than they had been before the strike).

Though angry and bitterly disappointed, the PFA decided to make their next move towards freedom via the law courts. In 1960 Newcastle United refused to grant England international George Eastham a transfer.

When the Football League declined to help him, Jimmy Hill and PFA secretary Cliff Lloyd decided to challenge the retain-and-transfer system in a court of law for the first time in 50 years.

It was quite a gamble, as the previous attempt in 1912 had ended in ignominious failure for the union and near bankruptcy. However, by the time the case came to the High Court, Eastham had been granted his transfer and was an Arsenal player.

Although he might have decided not to press ahead, he felt there was a principle at stake worth fighting for – the illegality of the retain-and-transfer system. Lloyd was to prove the critical witness, however.

Considerable amounts of detail had to be communicated to the judge and various legal officials.

In a sense, the case turned into a complete review of the workings of professional football; all the legal preparation, submissions, groundwork, and casework could have come to naught without a ‘star’ expert witness.

It would be Lloyd’s responsibility to put forward the arguments, convictions, and beliefs of the players, which had been for so long ignored, ridiculed, and derided by countless League directors and FA administrators, whose own points of view had prevailed for over three-quarters of a century, simply because there had been no real opportunity to counter them, their ignorance bolstered by myth and crude economic power.

Nervous, sometimes to the point of panic, in the hours before the trial, Lloyd was calm and collected once in the witness box.

With admirable common sense and convincing logic, he countered the League’s claims that removing the retain and transfer system would be detrimental to competition and the professional game as a whole.

After the trial, which found the existing contract system to be a “restraint of trade,” the judge praised Lloyd as “a witness who seemed to me to be more in touch with the realities of professional football and particularly the considerations affecting the supply and interests of players than any other witness.”

It was the beginning of the end for the system that had benighted the lives of thousands of professional footballers since the turn of the 20th Century, and it was Cliff Lloyd’s finest hour.

The 1970s – Passion is in Fashion

Building on the victories of the 1960s, the union gained a stronger foothold in the game’s running and devised a way to present its members in a more favorable light. Complete freedom of contract would be a long time coming.

Although the Eastham case had succeeded in establishing that reform of the prevailing arrangements was now a matter of when, not if, the achievement of such reform was to prove difficult.

But heartening for the PFA was the fact that it was now a full participant in the process. In 1972 a Joint Negotiating Committee was set up to work with representatives from the football league towards freedom of contract.

Though at times it was a frustrating, even tortuous, business, there at least now seemed an end in sight. A vital member of that committee would be Derek Dougan, who in 1970 succeeded Terry Neill as PFA chairman.

Dougan was a keen advocate of the ground-breaking Chester Committee Report (CCR) on the future of the professional game, produced in 1968.

This committee had been set up after the FA and Football League had called on the government to take action due to the “deteriorating financial position of the game and the need for cash for its improvement and administration.”

The report’s far-reaching suggestions had not been welcomed by football’s authorities, which had wanted money rather than advice. By contrast, it bolstered the PFA’s growing belief that it had an influential role in the game’s future.

It had concluded that the PFA was, in many ways, a typical trade union, advising members about contracts, dealing with settlements under the Industrial Injuries Act, and helping players get engagements upon the expiry of their contracts.

Yet, in specific fundamental ways, the organization differed from other, more traditional unions. Players’ contracts were now individually negotiated in a highly competitive but limited market. Thus the role of the PFA was to try to ensure that certain general conditions were observed.

Also, with the professional player’s working life tending to be much shorter than in most professions (players had often finished their careers by the age of 35), the CCR concluded that the PFA “has the peculiar problem of watching over the interests of boys at one end and men whose careers finish in the early 30s at the other”.

Most complicated of all, “many aspects of the rules of the playing of football may affect the remuneration and conditions of professional footballers without the connection being direct or obvious.”

For the PFA, the CCR was seen as an opportunity for it to tackle diverse yet related problems, such as the disciplining of players by both the ruling bodies; the behaviour of its members on and off the field and their public image; the financial security of members; and their education before, during and after their playing careers.

By doing so, the players’ body would address questions that concerned the health of professional football as a whole — an issue the game’s governing bodies, concerned as they appeared to be only with cash and competitions, seemed barely alive too.

The PFA embraced the CCR wholeheartedly and, at its 1969 AGM, outlined the following demands: changes in the option clauses in players’ contracts so that they were placed on an equal footing with clubs where renewal was concerned; a proper pension scheme to replace the Provident Fund; a new standard form of contract, plus a complete reform of the structure of disciplinary procedures.

The first fruits of the campaign were reaped in 1971 following the FA’s dramatic ‘clean-up’ operation on the pitch where discipline was concerned.

The PFA objected to the subsequent sudden and unannounced changes made. These affected the application of the game’s laws, resulting in hundreds of dismissals and yellow cards in the first few months of the season.

A joint committee called Independent Disciplinary Tribunal was set up to include representatives of the FA, the Football League, and the PFA.

To be involved in matters normally the preserve of the FA but involving the on-the-field fortunes of its members was a significant step forward for the football organisation. In 1972 Liverpool’s center-back Larry Lloyd made history by being the first player to overturn a suspension at the newly formed tribunal.

Significant moves on the education front also occurred. In 1971 Bob Kerry became the PFA’s first education officer charged with developing services for any member or ex-member wishing to undertake vocational training. It would lead in 1979 to the formation of the Footballers’ Further Education and Vocational Training Society.

There was also a move to start promoting the image of the pro footballer in a more imaginative way. As a result, in 1970, a Football Hall of Fame was established on Oxford Street, London.

This joint venture involved the PFA, the FA, and a group of private investors. The PFA was to receive 10 percent of the profits, but the venture closed its doors in 1972 due to a lack of support from the public. One feature of the doomed hall that didn’t disappear was the idea of a ‘Players’ Player of the Year, chosen initially by the PFA committee.

Dougan, along with Cliff Lloyd and Eric Woodward of Aston Villa, decided to build an event around the idea of every player having a say in who they thought merited the prize of top man each year.

So in 1974, the PFA Awards Dinner was inaugurated, a lavish, black-tie event held in one of London’s best hotels in Park Lane and transmitted live by ATV.

Dougan would later cite it as one of his proudest achievements: “The footballer’s image as a thick-headed yokel who needs constant discipline and cannot be trusted to manage his affairs is a distant throwback.

The actual image belongs to the PFA Awards night. Anyone who doubts the social progress of the modern footballer has only to switch on the Player of the Year Awards on ITV, without doubt, the best night on the sporting calendar.”

When pro football was coming under increasing criticism for its dour, defensive, not to say violent, tendencies, the players picked as their first winner that arch exponent of the crunching tackle, Leeds United’s Norman ‘Bite Yer Legs’ Hunter.

Hunter’s selection was probably not consciously designed to make a point. Still, his award indeed represented a public thumbing of the nose to critics at all levels, particularly those in the press and the media. Players were starting to do things for themselves.

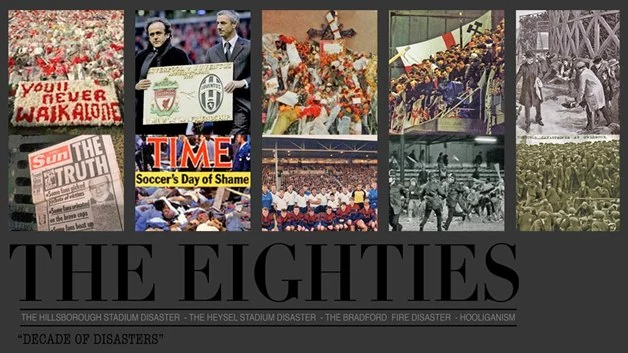

The 1980s – A Game in Crisis

As economic recession hits Britain, football finds itself struggling in the face of hooliganism, drastically falling attendance figures, and a series of devastating crowd disasters.

The 1980s were great years for the PFA and its members but terrible ones for the game itself. On the terraces, the scourge of hooliganism had been wreaking havoc for a decade or more, and the events at Heysel plunged the game into almost terminal depression.

The smoke still rises from the charred remains of the main stand at the Valley Parade football ground after the blaze, which left over 50 dead and more than 200 injured, was brought under control. The tragic deaths of many fans in the Bradford City fire and at Hillsborough underlined that something was rotten at the heart of the game.

Meanwhile, the economic recession was cutting a swathe through smaller clubs as bankruptcies loomed from Bristol City to Rochdale. However, for the PFA and its members, it was a time of immense change and opportunity.

In 1981 the new Players Standard Contract was introduced, and, for the first time since the 1890s, players found themselves free to seek a move to a new club once their existing contract had expired. Negotiations had been long and hard ever since the Eastham judgment in 1963.

However, when the clubs understood that the transfer system would remain for players in contract, they conceded the restrictive retention clause that had caused so much grief down the years.

At the end of their contracts, players could now exercise their option to leave their club. If the club offered the player new terms at least as attractive as the old ones, then the selling club was still entitled to a transfer fee.

A tribunal would then decide the appropriate figure if the clubs could not agree upon a fee. When under contract in this new arrangement, players or their agents were explicitly not allowed to initiate transfer moves; it was up to the potential buyer to approach the club directly where this player was based.

This system would last until the ground-breaking Jean-Marc Bosman case in 1995. It was a historic shift in relations between players and clubs and marked the start of the modern era for professional players.

In 1980 the Players’ Cash Benefit scheme was being put to area meetings of players for their enthusiastic endorsement.

The new scheme provided pro players with something no other ‘industrial’ worker, other than deep-sea divers, could boast — a lump sum payment on attaining the age of 35, based on years of service multiplied by average earnings, which was equivalent to between three and four percent of a man’s total earnings, plus a death-in-service benefit of up to £15,000.

A five percent levy on transfer fees provided the premium for the scheme, so players contributed nothing to it. Ironically, the despised transfer system that had more or less called the union into existence was now paying for each man’s security! Further benefits followed for members during the next few years.

In 1985 a joint initiative between the PFA and the Football League to provide a private contributory pension scheme for all full-time professional footballers was started, known as the PFA/Football League Players’ Retirement Income Scheme.

In 1986 the Footballers’ Further Education and Vocational Training Scheme (FFE+VTS) was initiated, one of the three welfare schemes the PFA operated for members.

The additional two were the Benevolent Fund, which provided grants to members or former members needing financial assistance, and the Accident Insurance Fund, who assisted former players experiencing medical difficulties due to a previous injury.

Also, in 1986, Football in the Community was formed by the FFE+VTS. The Football League and Nationwide Conference began developing community schemes offering a wide range of sports and social-based activities supported by the PFA.

Incorporated as a separately registered charity, it was allocated an annual funding budget from the PFA, encouraging ex-players to participate. Two years after its formation, it had helped create 350 jobs at 35 clubs, helping former players such as Duncan McKenzie, Tony Currie, and Alex Williams to keep contributing to local life.

In 1989 the financial department of the PFA – PFA Financial Management Limited – was established, handling anything from personal investment to advice on signing contracts. The PFA had thus become football agents.

In such ways and others, the PFA grew quantitatively and qualitatively as no other union organization during these troubled years could. Moreover, when Gordon Taylor took command, its secondary role as a quasi-guardian and protector of the industry its members worked in would be considerably enhanced.

Much of this confidence stemmed from its healthy bank balance, the lion’s share of which now came from TV revenues passed on to it by the Football League and the FA.

While the latter bodies tended to divide up their shares into relatively insignificant portions, the PFA’s share, averaging between £300,000 and £400,000 per annum, arrived in one lump, a significant proportion of which was invested; so there was a fair amount left that could be loaned to floundering clubs.

Football’s crisis was the country’s crisis too. The recession brought large-scale unemployment and caused widespread despair. Football clubs were often the focal points of their communities; keeping them going was a small but sometimes significant contribution to keeping up people’s morale.

As Taylor put it, “The League believes in natural wastage, whereas we think that clubs have a debt to supporters to stay in existence.”

This, according to Taylor, was the true “identity” of football, confirmed by the fact that on many occasions, he was welcomed more by supporters and councilors than the club’s directors.

Best Footballers Over The PFA History

In 2017, the PFA asked each club to nominate their club’s best player over the last 100 years. Each Football League club has one entry for its favorite player. A survey of supporters of current, as well as former, league clubs was conducted to determine the PFA’s number one player.

The theme to the film Local Hero has blasted out of the public address system at St James’ Park for a decade or more. It could apply to any number of Newcastle United legends over the years, from Jackie Milburn, Malcolm Macdonald, and Kevin Keegan to Tino Asprilla; in the supporters’ eyes, though, the real, local hero is Alan Shearer.

Across northern England, the Blackburn fans who inhabit Ewood Park are of a similar mind: a club who have been graced by the likes of Simon Garner, Bryan Douglas, Derek Fazackerley, and Henning Berg also plumped for Alan Shearer as the best player in their history. He would probably be the all-time favorite at Southampton, too, if it were not for Matthew Le Tissier’s longevity, loyalty, and breathtaking skill.

Meanwhile, in west London, there is not much that unites the followers of Queens Park Rangers and Brentford, but both supporters voted Stan Bowles as their favorite. Which is quite something for a boy born in Manchester of whom one of his earlier managers said: “If Stan could pass a betting shop the way he can pass a ball, he’d have no worries whatsoever.”

At Blackpool, Stoke, and Preston, their obvious choices were knighted by the Queen: arise Sir Stanley Matthews and Sir Tom Finney, England team-mates during the Forties and Fifties; the fans of Macclesfield Town applied the prefix themselves to ‘Sir’ John Askey, a long-serving midfield player whose career spanned their non-League and early Football League days.

The countrywide debate was sparked as part of the centenary celebrations of the players’ union, the Professional Footballers’ Association, and their One Goal One Million charity campaign. The PFA canvassed the opinions of the supporters of present and some former League clubs about their No 1 player.

How you decide between colossuses such as Sir Bobby Charlton, George Best, Denis Law, Eric Cantona, Bryan Robson, and Cristiano Ronaldo at Old Trafford is anybody’s guess. In the case of Manchester United, the fans went back more than half a century to plump for Duncan Edwards.

That shows a degree of understanding of the history of your club.

How can more than a century’s worth of selfless endeavor be distilled into one name? Who is more important to the club: a player who makes 600 appearances as a steady center-half, or the crowd-pleasing No 10 who will beat six opponents and put his cross into the side-netting? Bobby Moore or Tony Currie? Put simply, what does make a local hero?

PFA Club-By-Club List In Full

Accrington Stanley – Chris Grimshaw

Arsenal – Thierry Henry

Aston Villa – Paul McGrath

Barnet – Dougie Freedman

Barnsley – Neil Redfearn

Birmingham – Trevor Francis

Blackburn Rovers – Alan Shearer

Blackpool – Stanley Matthews

Bolton Wanderers – Nat Lofthouse

Boston Utd – Paul Bastock

Bournemouth – Ted Macdougall

Bradford City – Stuart McCall

Brentford – Stan Bowles

Brighton – Peter Ward

Bristol City – John Atyeo

Bristol Rovers – Devon White

Burnley J- immy McIlroy

Bury – Chris Lucketti

Cambridge Utd – Dion Dublin

Cardiff City – Phil Dwyer

Carlisle Utd – Hugh Mcilmoyle

Charlton Athletic – Derek Hales

Chelsea – Gianfranco Zola

Cheltenham Town – Neil Grayson

Chester City – Ian Rush

Chesterfield – Ernie Moss

Colchester – Karl Duguid

Coventry City – Steve Ogrizovic

Crewe – David Platt

Crystal Palace – Ian Wright

Darlington – Alan Walsh

Derby County – Kevin Hector

Doncaster Rovers – Alick Jeffrey

Everton – Dixie Dean

Exeter – Alan Banks

Gillingham – Andy Hessenthaler

Grimsby Town – Matt Tees

Halifax Town – Paul Stoneman

Hartlepool Utd – Wattie Moore

Hereford – Ronnie Radford

Huddersfield Town – Denis Law

Hull City – Ken Wagstaff

Ipswich Town – John Wark

Kidderminster – Kim Casey

Leeds Utd – Billy Bremner

Leicester City – Steve Walsh

Leyton Orient – Lawrie Cunningham

Lincoln City – Andy Graver

Liverpool – Kenny Dalglish

Luton Town – Mick Harford

Macclesfield – Sir John Askey

Man City – Bert Trautmann

Man Utd – Duncan Edwards

Mansfield Town – Ken Wagstaff

Middlesbrough – Juninho

Millwall – Teddy Sheringham

Northampton – Joe Kiernan

Norwich City – Kevin Keelan

Nottm Forest – Stuart Pearce

Notts County – Don Masson

Oldham Athletic – Bert Lister

Oxford Utd – John Aldridge

Peterborough T- erry Bly

Plymouth – Tommy Tynan

Port Vale – Robbie Earle

Portsmouth – Jimmy Dickinson

Preston NE – Sir Tom Finney

QPR – Stan Bowles

Reading – Robin Friday

Rochdale – Reg Jenkins

Rotherham – Ronnie Moore

Rushden & Diamonds – Paul Underwood

Scunthorpe Utd – Jack Brownsword

Sheffield Utd – Tony Currie

Sheffield Wed – Chris Waddle

Shrewsbury Town – Arthur Rowley

Southampton – Matt Le Tissier

Southend – Steve Tilson

Southport – Eric Redrobe

Stockport – Luke Beckett

Stoke City – Stanley Matthews

Sunderland – Charlie Hurley

Swansea City – Ivor Allchurch

Swindon – Don Rogers

Torquay – Robin Stubbs

Tottenham – Jimmy Greaves

Tranmere Rovers – Ian Muir

Walsall – Alan Buckley

Watford – John Barnes

West Brom – Tony Brown

West Ham – Bobby Moore

Wigan Athletic – Arjan de Zeeuw

Wimbledon – Dave Beasant

Wolves – Steve Bull

Wrexham – Joey Jones

Wycombe W – Dave Carroll

Yeovil Town – Terry Skiverton

York City – Barry Jackson