In Scotland, football has a history dating back almost 600 years. Four separate acts of parliament attempted to curtail ‘futeball’ during the fifteenth century, demonstrating the game’s popularity long before it would be formally regulated and codified in the nineteenth century.

In the past, football has been enjoyed by monarchs (James IV and Mary Queen of Scots), as well as commoners, and it has been historically found as an activity throughout the country, from the Scottish Borders and the Western Highlands to the North East Lowlands and even the Shetland Islands.

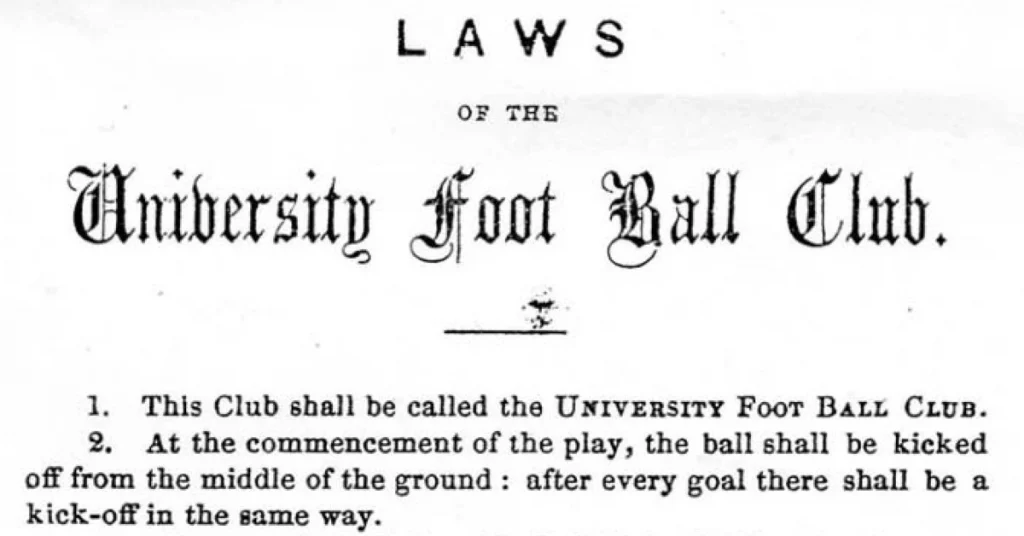

Scotland also boasts the world’s first known football club (Edinburgh, 1824), and the oldest existing football in the world (circa 1540) was found in Stirling Castle’s Royal Palace.

A silver medallion awarded in 1851 to the 93rd Highland regiment in celebration of their victory over Edinburgh University Football Club is the world’s oldest surviving football trophy. Clubs in Glasgow, Lanarkshire, and the south of Scotland adopted the Association code of Scotland football during the late 1860s.

Scotland Football In The 19th Century

The increasing urbanization that followed the industrial revolution finally began to intrude on the popularity of the crude version of Scotland football. Working men were better policed and had less free time and space to play the game. As a result, it began to wane in popularity.

Ironically, for a game that was always a common person’s sport, football was to survive and thrive in the elitist public school system in Britain.

Forms of football had been played at public schools since the 1600s. Still, it was in the 19th century that educationalists began to look at the sport as anything other than a nuisance, though the change in attitude was hardly uniform. For example, Samuel Butler, head of Shrewsbury School between 1798 and 1831, described football as fit only for butcher boys.

But by the 18th century, the public schools’ notorious lack of discipline began to be addressed. Teachers had turned to sport as a vehicle to tackle this problem. As football was already second only to cricket in popularity, teachers were happy to exploit the game to instill notions of discipline and loyalty into pupils.

The building of a national railway system in the middle of the nineteenth century allowed schools to play with each other, but this gave rise to new problems. Each school had its own version of the game. Some permitted handling of the ball, while others preferred a dribbling game.

This problem continued in higher education when pupils from different schools tried to form football teams, with students all knowing different game variations.

To combat this, a meeting was held at Cambridge in 1848 to draw up an acceptable set of rules, with dribbling favored over the handling of the ball. This was the first of many attempts over the next twenty years to establish a coherent body of laws for the game.

An increasing sense of civic responsibility accompanied the Victorian schools’ appetite for the sport. Pupils left the schools filled with the desire to tackle the social problems of the day.

To do this, they used sport, just as their masters had, taking it back to the working-class communities where the game originated.

The Last Of The Amateurs

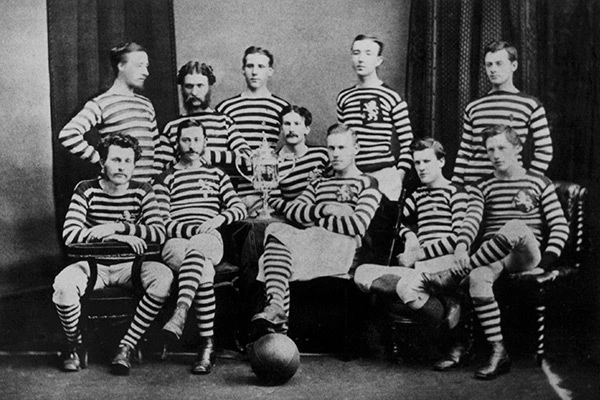

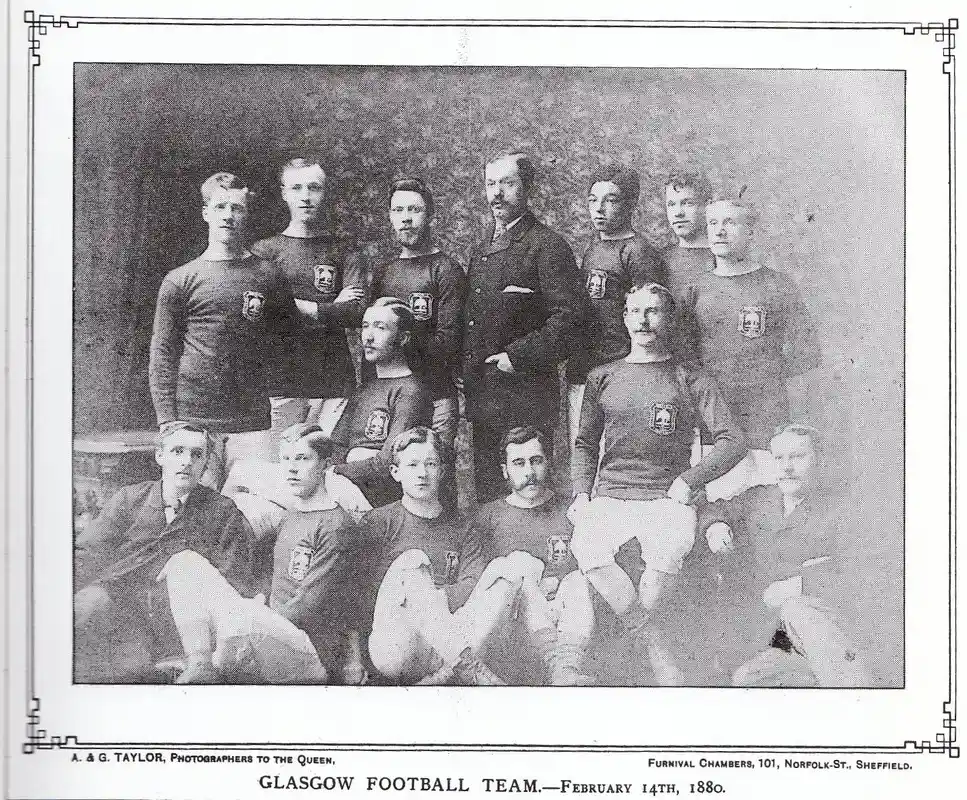

The first football team in Scotland was Queen’s Park, formed in 1867. However, they had another year to wait before they played their first competitive game against a team called Thistle in August 1868.

After Queen’s Park, clubs began forming, and games were initially arranged on a friendly basis. As national transport systems spread throughout the British Isles, international meetings became inevitable.

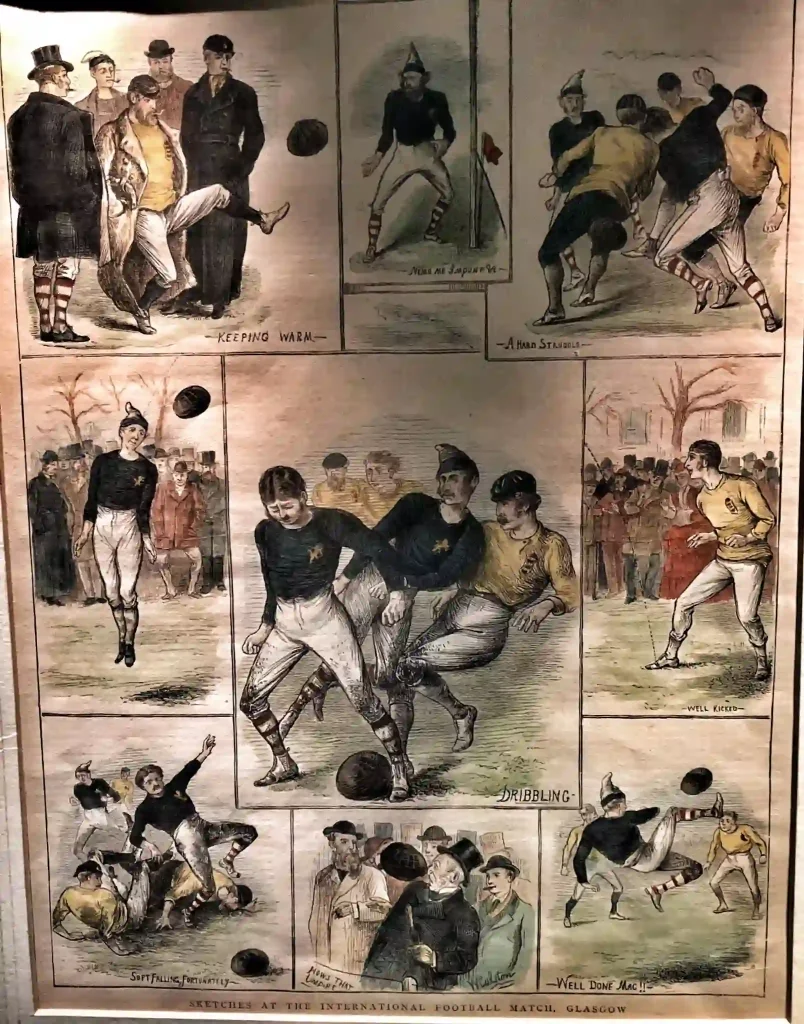

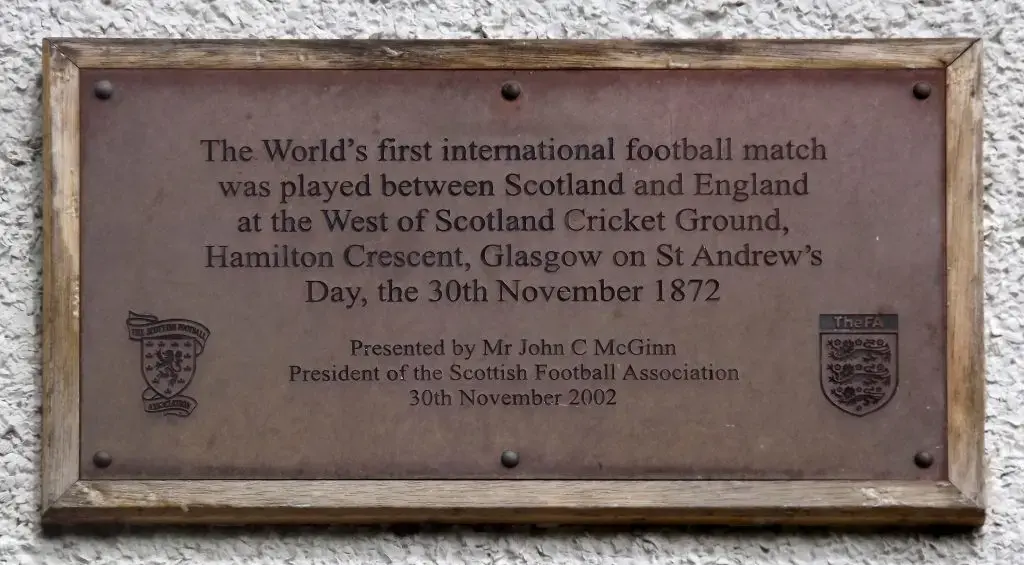

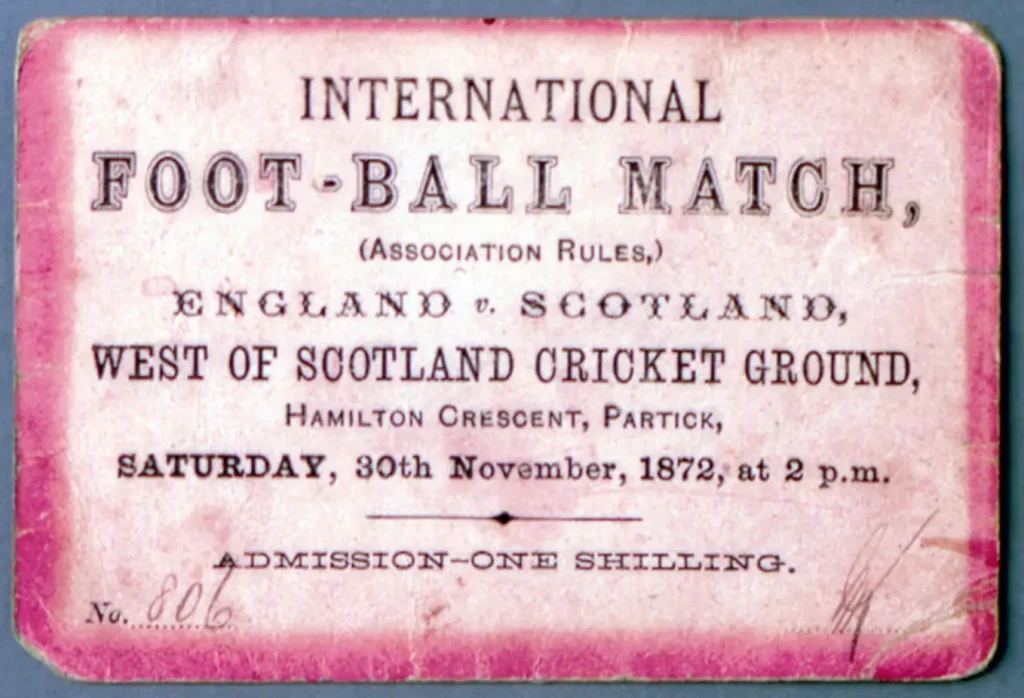

The first official meeting of the `auld enemy’ occurred on Saint Andrew’s Day in 1872 when Queen’s Park arranged a game at Hamilton Crescent cricket ground.

Two years earlier, the Secretary of the English Football Association, Charles Alcock, had written to the Glasgow Herald to suggest an international game between the neighbors.

Alcock himself arranged four games in London. He even picked the Scotland Football team from Scots plying their trade in England. It is no surprise then that England won all four matches.

The `Alcock internationals’ have no official standing, however. So it was that St Andrew’s day meeting in 1872 which saw the first genuine international between Scotland and England, with Queens Park representing the Scots.

In exchange for the use of their soccer field, Queen’s Park offered the West of Scotland cricket club £10 and a further £10 if the game took more than £50.

The scoreless draw was attended by 4000 people, who paid £103. The match’s success ensured that it would be played on a regular basis in the future. In the first twelve internationals against England, Scotland won eight and lost only two.

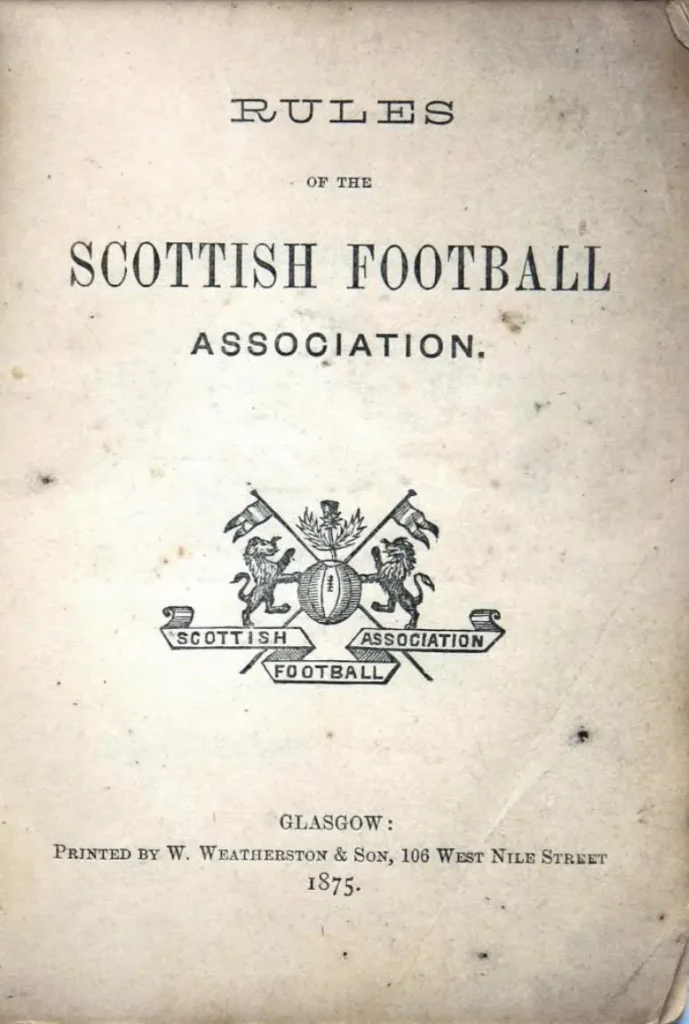

The clash also provided the impetus for the domestic game north of the border to adopt a more competitive approach. Another result of 1872 international was the establishment of the Scottish Football Association.

After the match, Queen’s Park called a meeting attended by representatives of the country’s leading clubs of the time – Clydesdale, Vale of Leven, Dumbreck, Third Lanark Rifle Volunteer Reserves, Eastern, Granville, and Rovers – to thrash out the details.

It was at this meeting that the Scottish Football Association was founded as well as the Challenge Cup competition, which was later renamed the Scottish Cup.

In 1883 and 1884, Queen’s Park reached the English FA Cup final, but were beaten both times by Blackburn Rovers before the SFA decreed, in 1887, that clubs “belonging to this Association shall not belong to any other Association.”

Queen’s Park had won the Scottish Cup six times by that time, with Vale of Leven taking the trophy away for three years. But by the end of the 1880s, Queen’s Park’s dominance of the Scottish game was nearing an end. Glasgow Rangers were formed in 1872, and Celtic in 1888.

In 1893 while Queen’s Park claimed their last Scottish Cup success, Celtic won their first league title in the third year of the competition. The day of the gentleman amateur, so typified by the Hampden club, was drawing to a close.

Scotland Football Turning Professional

The introduction of competition into the game, in the form of the Scottish and English Cups and the establishment of league contests, boosted an already healthy public appetite for football. In turn, competition emphasized the need for good results and increased the demand for professionalism.

The English FA eventually bowed to the calls for a professional set-up in 1885, and English clubs, impressed by the playing ability and teamwork shown by the Scots in meetings with England, were soon looking north to snag their own “Scotch professors” of the game.

For the players, the temptations were obvious. Not only would they be offered money to play, but they would be found jobs in their trade. In 1890 Wilson, a keeper with Vale of Leven, was offered £3.10/- per week for playing and £1 a week to work as a dyer by Blackburn.

James Oswald, a striker with Third Lanark, was offered a tobacconist’s shop with £500 of stock and two guaranteed seasons for £160 each season if he signed for Notts County.

That compared with 36/- wage packet for a 54-hour week for a Glasgow fitter or tuner. No wonder many footballers were happy to move south. Despite the English influence, the Scottish game remained steadfastly opposed to the introduction of professionalism until 1893.

The most vocal opponents to its introduction were Queen’s Park and the Scotland Football press, who regularly described footballers tempted south as “base mercenaries” or “traitorous wretches.”

But for all the official disapproval, under-the-counter payments were rife. Players who had to take days off work to play were allowed `broken time’ payments – a system frequently abused.

When Hibs won the Scottish Cup in 1887, their opponents called a private detective to investigate rumors of financial irregularities at the Edinburgh club. He found the club paid one Hibs player, Groves, an apprentice stonemason, a £1 broken time payment for missing three days at work. Yet he would typically only earn between 7/6d to 10/- a week.

Queen of the South Wanderers was later convicted of making broken time payments to two players who were in fact, unemployed.

Despite SFA efforts to crack down on such abuses, Scottish football’s amateur status was increasing pressure as the more prominent clubs became more and more profitable.

By 1890 Celtic were garnering £5000 per year, the most successful club in Britain then. Only so much money could be diverted into improving the ground and charity contributions. Inevitably Celtic and Rangers were keen to use their finances to improve their teams.

The proponents of amateurism were fighting a losing battle. In 1893 professionalism was approved in Scotland football, and within 12 months, 83 clubs had registered almost 800 professional players.

By the 1890s, the Scottish football game began to assume what was to become a familiar pattern, dominated by the two Glasgow giants, with Celtic taking four league titles, while Rangers took three and three Cups for good measure.

Mondo Football

By the beginning of the twentieth century, football was Scotland’s most popular sport, and inevitably the game began to spread worldwide, following British ex-pats.

The game took off in Britain in the 1870s and spread to Europe. The first Danish club was established in 1876 by British residents. The game was established in Sweden after natives watched members of the British Embassy play the game in Stockholm’s public parks.

The first modern club in France was established in 1872 in Le Havre following a game with visiting British sailors. Within a generation, the game had established healthy roots across the continent. In 1897 Juventus was formed from a group of Turin students and local British residents.

The forerunner of AC Milan quickly followed, again formed by locals and ex-pats. This pattern was repeated throughout the continent and further afield.

An English professor at Montevideo University founded the first Uruguayan team. Penarol emerged out of a sporting club formed by four British railway workers.

British football teams encouraged European and South American soccer growth by arranging tours. In 1898 Queens Park played in Scandinavia, while Southampton became the first British team to play in South America in 1904. Soon teams from abroad were touring Britain, as a Canadian team did as early as 1888.

As the game spread, the need for some formal body to regulate it worldwide was recognized. So, in 1904, FIFA was established in Paris. Ironically the British football associations took no part in the initiative. By the time of the first World War, football had been introduced to every continent, though it remained most popular in Europe and South America.

Within 40 years, the game nurtured in the English public school had been reclaimed by the working class and spread throughout the planet. football was a worldwide phenomenon.

Scottish Football Between The Wars

Football in Scotland did continue throughout World War One, but haphazardly, with the Second Division scrapped and many of the First Division sides struggling to field an entire team as players signed up for the army. The entire Hearts team signed up on the same day, and many of them were to die in the killing fields of France.

Despite the wars, the game flourished between them. An incredible 149,415 spectators watched Scotland play England at Hampden in 1937, a European record. Celtic beat Aberdeen in the Scottish Cup final a week later in front of 147,365 fans.

In the international arena, the interwar years saw one of Scotland’s most remarkable triumphs when the “Wembly wizards” recorded an impressive 5-1 win over England at Wembley in 1928, thanks to a hat-trick from Alex Jackson and a brace from Alex James.

The goals capped an outstanding performance by the Scots, with the defense equally deserving plaudits for the way they handled the menace of the legendary Dixie Deans. Ironically, both sides had started the Home International tie seeking to avoid the wooden spoon that season, as Wales had already claimed the championship.

While British football flourished at the domestic level, the respective football associations showed a remarkably insular attitude towards international competition. Scotland’s first football international against opposition other than England, Wales, and Ireland only occurred in 1929 when they beat Norway 7-3 in Bergen.

After the war, the British associations decided not to play against Germany and Austria, though no other European teams supported their embargo. As a result, the British FAs withdrew from FIFA. They rejoined the organization in 1924, but after four fractious years, they again withdrew and did not join again until 1946.

As a result, British teams did not compete in the three interwar World Cup competitions. Uruguay was the first nation to claim the title, beating Argentina 4-2 in front of 90,000 fans in Montevideo in 1930.

The Italians won in 1934 in Rome and 1938 in Paris in competitions heavily politicized by Mussolini’s fascist regime, which was keen to trumpet the side’s success as a reflection of their political masters. It would not be the last time politics and the game would be bedfellows.

The Post-War Boom Of Scotland Football

The immediate post-War years saw football in Britain enjoy its greatest-ever boom period. It was a time when people longed to return to the everyday lives they had led six years before, and the populace was desperate for entertainment. Despite great austerity, a climate existed where the mass pleasure of going to football could flourish again.

Stadiums up and down Scotland were packed every Saturday, often to hazardous levels; very little care went into spectator comfort or safety.

In a period of post-War reconstruction, it may have seemed wasteful to use sparse resources to shore up decrepit football grounds. In many cases, stands were held together by rusting girders, and the terracings were crumbling in disrepair, but this did nothing to deter the vast crowds hungry for Scottish football.

Rangers played to an aggregate of over one million people in a season on several occasions in the late Forties and early Fifties. In 1952, 136,000 supporters crammed into Hampden to watch the Motherwell – Dundee Scottish Cup Final.

In England, all-time peak attendance reached over 41 million people in the 1948-49 season. As early as 1945, British football was given a sharp reminder that football abroad had progressed to extremely accomplished levels.

The British had been accustomed to more than 50 years of unchallenged superiority in the sport. Hence, the arrival of a well-drilled, skilled, and highly competitive Moscow Dynamo side came as a shock.

The Russians drew huge crowds on their travels in the UK, the tour culminating in a highly entertaining 2-2 draw at Ibrox, which attracted 90,000 fans.

Despite this warning, British footballing authorities remained very insular in their outlook, and the same arrogance which had seen the first three World Cup competitions take place without the British prevailed.

Founding Fathers Humbled

Any doubts that the rest of the world had caught up, and in many cases surpassed, the British in footballing ability were dispelled during the World Cup of 1950.

England’s surprise 1-0 defeat at the hands of the USA perfectly illustrated the game’s growth and development worldwide. The incredible skill and technique of the South Americans produced performances far in advance of any of the Home Nations.

This point was hammered home when the marvelous Hungarian side containing Bozsik, Hidegkuti, and Puskas came to Wembley in 1953 and swept the English aside 6-3 with a display of sublime skill. There could be no dispute that primacy had slipped away from the game’s founding fathers.

The Hungarians came to Hampden the following year, running out comfortable 4-2 winners. The gulf in standards was rubbed in horrifically during the 1954 World Cup in Switzerland.

Scotland football portrayed all the traits that blighted the game’s development with their narrow-minded and outdated approach to the competition.

The preparation was atrocious. Scotland only traveled with 13 players and displayed a complete lack of tactical awareness, losing first to Austria, then being trounced 7-0 by a talented Uruguayan team.

As the 1950s grew increasingly prosperous, people became more leisure-minded, and several alternatives to football became available for those with disposable incomes. Match attendances slumped as a result.

Scotland Football History Of The European Cup

The advent of televised games also hurt crowds. With the best of the available football being shown on television, audiences became more discriminatory, and lower league teams lost crowds much faster. The Celtic v Clyde Scottish Cup final of 1955 was the first televised game in Scotland.

Improvements in the transport network and the increase in car ownership made it much easier to travel to see the nearest big team rather than lend support to the local side.

Glasgow is a prime example of such an occurrence, with thousands traveling to the city each Saturday to cheer on the hugely popular Celtic and Rangers and turning their backs on the plethora of smaller clubs on the west coast of Scotland.

The advent of the European Cup in 1956 did much to introduce British sides to the new successful methods being adopted by their continental rivals. The competition was established by the French sports magazine L’Equipe, who sent invitations to the top European clubs to participate in the inaugural contest.

Hibernian were the Scotland football representative (and Britain’s sole representatives), with English sides once again prominent by their absence. The Football League persuaded league champions, Chelsea not to enter for fear of interfering with home commitments.

Hibernian was one of the few teams in the UK willing to look abroad for inspiration. They had toured Brazil in 1953 and invited several foreign clubs to play in Edinburgh.

Their reward for their progressive thinking and fine attacking play was a place in the semi-finals, where they lost out narrowly to Rheims of France. Nevertheless, the tournament immediately captured the public imagination throughout the continent and attracted huge crowds.

Real Madrid lifted the first European Cup, and the giants of Spanish football dominated the early competitions, winning the next four as well. Real’s five-in-a-row run culminated in what many regard the finest ninety minutes of football ever played. The 1960 European Cup final was played at a packed Hampden Park.

A hugely appreciative Scottish football crowd cheered in awe as Alfredo Di Stefano, Ferenc Puskas, and Francisco Gento orchestrated the 7-3 victory over Eintracht Frankfurt. The German side had decimated Rangers 12-4 on aggregate in the semi-final, but their excellence proved no defense against the incomparable Real Madrid.

The growing lure of European competition soon saw the establishment of the Cup Winners’ Cup and the Inter City Fairs Cup, which later became the UEFA Cup. With valuable lessons eventually being learned from encounters with continental clubs, the increasing development of professionalism entered football management in Britain.

Scotland football, however, continued to struggle at the international level. Sweden’s 1958 World Cup finals saw Scotland take their first point in the competition with a draw against Yugoslavia, but they lost out to both Paraguay and France.

Northern Ireland and Wales reached the quarter-finals in Sweden, the Irish winning a famous victory over the Italians. The world was first introduced to the remarkable talents of the 17-year-old Pele in Sweden, and his mesmerizing and advanced skills helped the Brazilians to victory.

1967 Was Scottish Football Best

Resistance to television coverage of football was significantly greater in Scotland than in England. With the resulting loss of fans from the terraces, only some were convinced that the income from television compensated.

In the Sixties, TV made its seminal impact on the game and secured millions of armchair fans around the globe. The European Cup final of 1960 and the World Cup in 1966 were among several critical moments in establishing the popularity of televised football.

TV coverage grew more saturated and sophisticated, and with football facilities remaining very poor, attendances began to decline still further. Glasgow Rangers reached the final of the first-ever Cup Winners Cup in 1961 but were thwarted by Fiorentina.

The Scotland football team failed to qualify for the 1966 World Cup finals in England, so the 1967 tie between the sides carried an extra frisson when Scotland went to Wembley to face the recently crowned World Champions.

The English World Cup triumph of 1966 caused great rancor north of the Border, so it was extra sweet to see the `auld enemy’ humbled 3-2 and with style. Rangers’ Jim Baxter delighted the Scots in the crowd with his teasing play and contemptuous ball juggling.

Scotland could have pressed their advantage home with more goals, but they chose instead to adopt the posture of strutting matadors toying with their opposition. The Tartan Army loved it. 1967 also saw what was perhaps the greatest ever Scottish footballing achievement, when Celtic became the first British club to win the European Cup.

Jock Stein had taken over at Celtic Park in 1965 after successful managerial stints with Dunfermline and Hibs and quickly molded Celtic into the dominating force in Scottish football.

Jock Stein’s knowledge of the game, tactical awareness, and fantastic man-to-man management guided Celtic to the European final in Lisbon against Inter Milan. The Milanese team guided by Helenio Herrera had progressed courtesy of their sterile defensive style of play, which contrasted markedly with the attacking elan of the Scots.

The game started poorly for Celtic, going a goal behind from a penalty after just seven minutes. Celtic then carried the game to the Italians and, with the width of their play, stretched the heavily-manned defense of Inter.

The Scots attacking play was rewarded when full-back Tommy Gemmell leveled the score with a blistering drive, and, with six minutes to go, Chalmers re-directed a Murdoch shot into the net, and Celtic were the kings of Europe.

In that same year, Rangers reached the final of the Cup Winners’ Cup, where they were unlucky to lose out 1-0 in extra time to Bayern Munich.

Under Stein, Celtic won an incredible nine league titles in a row ( 1965-66 to 1973-74) and reached the European Cup final again in 1970, where they lost to Feyenoord 2-1. Celtic’s consolation was their semi-final victory over Leeds United. The national press was heralding the English side as certain winners of the tie.

Celtic followed their 1-0 win at Leeds with a 2-1 victory at Hampden in front of an ecstatic crowd of 134,000.

More European Glory From Scottish Teams

Rangers were to emulate their city rivals’ European success in 1972 when they lifted the Cup Winners’ Cup. In a splendid run to the final, they disposed of Sporting Lisbon and Torino and revenged Bayern Munich, for the final of 1967, in the semis.

Barcelona was the host city for the final, where the Glasgow side defeated Moscow Dynamo 3-2. Two goals from Willie Johnston and one from Colin Stein gave Rangers a 3-0 cushion. The Russians hit back well to score twice, but the Scots survived the onslaught.

The victory celebrations were unfortunately marred by violent clashes between the over-exuberant Scottish supporters, who spilled onto the pitch, and the Catalan police.

The year before Rangers’ European triumph had seen the terrible disaster at Ibrox, in which 66 people died in a stairway crush at the end of an Old Firm clash.

In the aftermath of the disaster, Scottish local authorities enforced severe restrictions on the number of spectators admitted to the more enormous grounds. The capacity of Hampden was cut from the 134,000 that had watched Celtic v Leeds the year before to 85,000.

The Scotland football team had not qualified for a World Cup since 1958. Brazil won twice (1962 and 1970), and the English won at Wembley in 1966. Willie Ormond took over the managerial reins at the international level from Tommy Docherty in 1973, and the initial signs were ominous.

Ormond’s first game in charge was against England, in a match to celebrate the Scottish Football Association’s centenary. Scotland lost 5-0.

The defeat gave Ormond a mandate to rebuild a team, which he did around midfielders Billy Bremner and Davie Hay, the defensive trio of Danny McGrain, Sandy Jardine, and the uncompromising Jim Holton.

The Scotland football team qualified for the World Cup finals in West Germany in 1974. It went through the tournament undefeated, beating Zaire 2-0, and drawing with Brazil 0-0 and Yugoslavia 1-1, only to be eliminated on goal difference.

The 1974 World Cup was notable for the emergence of the Dutch as a first-class footballing nation.

The core of the side who made it to the final against the host nation in such impressive style was made up from the successful Amsterdam club Ajax, who won the European Cup in 1971,’ 72, and ’73 and included such stars as Johann Cruyff, Johnnie Rep, Rudi Krol, and Arrie Haan.

The Germans came out on top in the final, and their premier club Bayern Munich went on to emulate Ajax by winning the next three consecutive European Cups. Bayern’s internationalists included Sepp Maier, Gerd Muller, and the great Franz Beckenbauer.

Argentina Debacle For The Scotland Football Team

Willie Ormond resigned as the Scotland national football boss in 1977, and Ally McLeod, who had proved himself a more than capable manager at Ayr United and Aberdeen, took over.

McLeod had inherited an excellent side, evidenced by a slick victory over England that year. World Cup qualification was once again ensured, at the expense of the then reigning European champions Czechoslovakia, and Scotland traveled to Argentina in 1978.

The Scotland football fans had high expectations, generated by victory over the Czechs and in the Home International championships. But disaster was to follow. A combination of overconfidence, lack of preparation, and a core of players past their best resulted in a humbling first-round exit.

The first game was lost to Peru and was followed by a shameful 1-1 draw with Iran, the Scots’ only goal coming from an unfortunate own-goal by an Iranian defender. More ignominy was to follow when Rangers forward Willie Johnston failed a random drug test and was sent home in disgrace.

A final match victory over Holland temporarily lifted the shadow over Ally McLeod’s squad, and Scotland fans had the consolation of seeing Archie Gemmill scoring the tournament’s best goal in that 3-2 win.

The impressive win over the eventual runners-up only heighten the frustration at the two prior performances. Holland was narrowly beaten in the final by the host nation, for whom Mario Kempes was the tournament star.

A Kick Up In The 1980s

Jock Stein took over the national side and rebuilt a solid and tactically wary side directed by the midfield strength of Graeme Souness and the guile of Kenny Dalglish.

Under Stein’s cautious hand, the Scotland football team carefully and competently picked their way through the qualifying matches and secured their passage to the World Cup in Spain in 1982.

Scotland got off to a good start with a 5-2 victory over New Zealand, but the defensive frailties hinted at in that game were ruthlessly exploited by Brazil, who hammered Scotland 4-1.

The sequence of results meant that the Scots had to defeat Russia in the final group match to proceed in the tournament. With the score at 1-1 in a tense game, Scotland defenders Willie Miller and Alan Hansen contrived to collide with one another and gift the Russians a goal.

Graeme Souness leveled the scores soon after, but despite another brave effort, the Tartan army was packing up for home at the end of the first round again. The Northern Ireland team showed the Scotland football team the way by progressing to the second round, with a memorable win over the host nation, Spain, on the way.

The Spanish finals will best be remembered for both of its breath-taking semi-finals when the Italians defeated Brazil 3-2, and the Germans came from behind against the stylish French to win on penalties after a thrilling 3-3 draw. Italy ran out comfortable 3-1 winners in the final.

On the domestic front, the 1980s saw a shift in the traditional balance of power in Scottish football with the emergence of Aberdeen and Dundee United as formidable footballing sides. Dubbed the `New Firm,’ both sides ended the Rangers/Celtic supremacy at home and made a considerable impact in Europe.

Dundee United produced some remarkable results in Europe, thrashing Borussia Moenchengladbach 5-0 in the 1982 UEFA Cup, then losing a 2-0 first-leg lead to Roma in the semi-final of the 1984 European Cup.

United reached the final of the UEFA Cup in 1987, where they lost out to Gothenburg. On the way to the final, they recorded a magnificent 3-1 aggregate win over Barcelona, which included a memorable 2-1 victory at the Nou Camp.

With Alex Ferguson at the managerial helm, Aberdeen went one better when they lifted the European Cup Winners’ Cup in 1983, defeating Bayern Munich on the way to a comprehensive 2-1 final victory over the mighty Real Madrid. Eric Black and John Hewitt scored either side of a soft penalty to the Spaniards.

Aberdeen reached the last four of the same tournament the following year but was squeezed out by an impressive Porto side.

Soccer’s Shame Moments

Two horrific events in 1985 would significantly impact the future of football in Britain and the environments in which the game was played.

A fire that consumed Bradford City’s main stand claimed the lives of 55 spectators. Then, only a few weeks later, 38 people died in a stampede of fans during the Liverpool – Juventus European Cup final in the Heysel Stadium in Brussels.

Immediately afterwards, ramshackle football stadiums up and down the land, which had stood unchanged for decades, were being pulled down and reconstructed.

Teams moved to new locations on the outskirts of cities, and those that could not move or immediately upgrade their grounds had their crowd capacities cut drastically.

English club sides were banned from European competition (Liverpool fans had triggered the crush with their attacks on the Juve supporters), which came as a massive blow to the game south of the Border.

English sides had dominated the European Cup in previous years, with Liverpool winning in 1977, ’78, ’81, and ’84, Nottingham Forest in 1979 and ’80, and Aston Villa in 1982.

Four years later, the disaster at Hillsborough followed, where 95 Liverpool fans died in a chaotic crush against the barriers, which were designed to provide a more secure environment.

Policing at big Scotland football games changed to combat the rising tide of hooliganism which had become fashionable during the early eighties, with more and more officers deployed in the streets surrounding the grounds, and clubs employed vast numbers of trained stewards to help control the crowds inside the stadium.

Perimeter fencing and cages, which had previously penned supporters in like animals, and bore much of the responsibility for the tragedy at Hillsborough, were ripped down.

Tragedy and Triumph

The Scotland football team once again qualified for the World Cup finals in Mexico in 1986. Jock Stein had masterminded another canny but successful qualifying campaign.

The final game of the qualifiers was against Wales, and with Scotland only needing a point to secure passage to Mexico, the 1-1 draw, thanks to a late Davie Cooper penalty, was sufficient.

But jubilation for the Tartan Army quickly turned to sorrow once the news was released that Jock Stein had died immediately after the game. The Scottish game had lost the most successful manager in its history. Alex Ferguson, who had done so well with Aberdeen, took temporary charge of the national team for the trip to Mexico.

The Scottish football team was pitted against West Germany, Denmark, and Uruguay in a formidable first stage dubbed dramatically “the group of death.”

Not surprisingly, Scotland did not progress further. Still, things may have been different if it were not for a glaring Steve Nicol miss against Uruguay and a terrible refereeing decision that ruled out a Roy Aitken’ goal’ against the Danes.

Argentina lifted the World Cup for a second time in 1986, thanks almost exclusively to the mesmerizing talents of Diego Maradona. The Argentinian No. 10 stamped his football magic on the tournament with a series of breathtaking displays.

1986 heralded the beginning of a revolution in Scotland football with the arrival of Graeme Souness as manager of Rangers. With the backing of his chairman David Murray, Souness took football in Scotland into the new age of commercialism and million-pound transfer fees that had taken root throughout Europe.

The age-old pattern of talented players leaving Scotland for foreign climes was reversed, with quality players from England and the continent taking the road North. Other football clubs in Scotland were slow to follow Rangers’ lead, and the head start given the Ibrox club has seen them almost wholly dominate the domestic scene since.

Andy Roxburgh was appointed manager of the Scottish national side, which qualified for a record fifth World Cup in succession. No other country on the globe can boast of such an achievement.

Of course, countries like Brazil, Italy, and Germany have participated in more finals, but their entry was guaranteed as either the holder of the trophy or the event hosts. It was hoped that the Scotland football team could mark such a proud achievement by progressing to the second round for the first time.

Sadly, It Was Not To Be

Scotland once again displayed their knack for shooting themselves in the foot when they crashed to a heartbreaking 1-0 defeat at the hands of Costa Rica. This calamitous performance was followed by a victory over Sweden and a brave 1-0 loss to Brazil.

The Germans went on to win the 1990 finals in Italy, seeing off Argentina again, dragged almost single-handedly to the final by the great Maradona.

European Championships

Under Roxburgh, the Scotland football team qualified for the final stages of the European Championships for the first time.

The tournament was held in Sweden in 1992, where Scotland equipped themselves well in narrow defeats by Holland and Germany and a great 3-0 win over the former Soviet Union.

Scotland failed to qualify for the World Cup, which the United States hosted in 1994. The choice of America, a country traditionally shunned soccer, was further evidence of the importance of high-level commercialism in the game.

The finals were a great success, and matches were played with packed and enthusiastic spectators in fantastic stadiums. The Brazilians went on to lift their first World Cup since 1970 after a penalty shoot-out with Italy, the first time the trophy had been settled in such fashion.

1996 saw Scotland again qualify for the European Championships, with Craig Brown as the national coach. The fact that the competition was being staged in England and the `auld enemy’ were drawn in the same group as Scotland gave the tournament some added spice.

Scotland started their campaign with a hugely creditable 0-0 draw with the Dutch. Then came the anxiously awaited Wembley showdown with the English, the first clash between the two nations since the traditional annual clash was scrapped back in 1989.

The Scotland football team crashed to a painful 2-0 defeat despite matching their opponents for much of the game. And who will forget Scotland captain Gary McAllister’s penalty miss just minutes before Paul Gascoigne scored England’s second goal.

Scotland defeated the Swiss 1-0 in their final match but cruelly missed out on qualification to the second phase on goal difference. The qualification campaign for the 1998 World Cup saw a familiar story, as Scotland qualified from a difficult group but failed to impact the final tournament itself.

A narrow 2-1 defeat from favorites, Brazil gave encouragement, but a 1-1 draw with Norway heralded a deeply disappointing 3-0 reverse from Morocco. Scotland failed to qualify for the second phase in eight attempts. It has been 24 years since Scotland qualified for the FIFA World Cup. Their next chance is in 2026.

This disappointment was followed by a narrow failure to reach Euro 2000, despite a 1-0 victory over England in a playoff. However, the damage was done in the home leg, and the Scotland football team again went out in a blaze of glory.

It has been 26 years since Scotland qualified for the UEFA European Championship. The last time Scotland qualified for the European Championship was in 1996, when they reached the group stage of the tournament held in England.

Their next chance is the upcoming European Championships in 2024.

How Many Years Since Scotland Beat England

It has been 24 years since Scotland beat England in a competitive international match. The last time Scotland beat England was November 17, 1999, when they won a European Championship qualifier by a 1-0. Since then, Scotland and England have played each other five times, with England winning three and drawing the other two.

England and Scotland have played 115 official matches against each other throughout history, more than any other nation. England has won 48 games to Scotland’s 41 in this fixture. There have been 26 draws (four goalless draws).

The next England-Scotland match scheduled is on September 12, 2023, which will be a friendly played at Hampden, Glasgow.

The Current Structure Of Football In Scotland

As Scotland’s national governing body, the Scottish FA is responsible for its overall administration. All levels of the game are promoted, fostered, and developed through the organization.

Providing access to football for players, coaches, and volunteers of all abilities, sexes, races, and genders is a key goal of the Scottish FA. The Scottish Cup competition and the operation of Scotland’s national football teams fall under its authority at the elite level.

In Scotland, senior league football is governed by the Scottish Professional Football League. Two senior cup competitions are run by the League – the Scottish League Cup and Scottish Challenge Cup – with 42 member clubs playing in four divisions.

In Scotland, non-league football is divided into four divisions: the Highland Football League, the Lowland Football League, the East of Scotland Football League, and the South of Scotland Football League.

In Scotland, women’s and girls’ football is governed by the Scottish Women’s Football League. The responsibilities include managing the Scottish Women’s Cup, Premier League 1 and 2, and youth competitions at the national and regional levels.